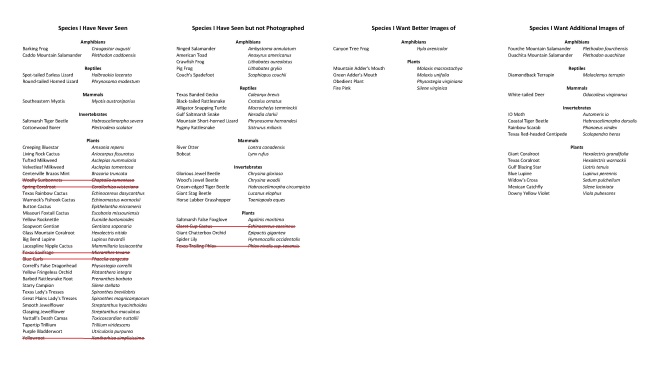

Targets Species: Texas Coralroot (Hexalectris warnockii) and Glass Mountain Coralroot (Hexalectris nitida)

Hexalectris warnockii

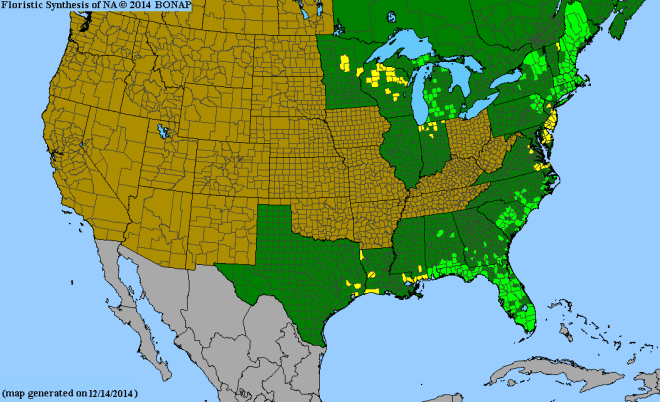

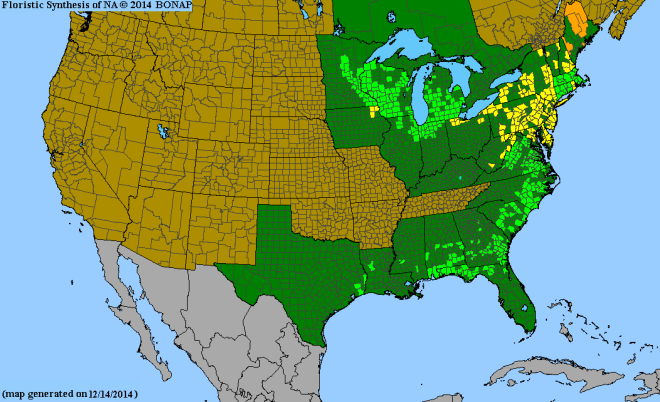

Texas boasts more species of the genus Hexalectris than any other state. Here 5 of the world’s 8 species can be found (these numbers change to 6 and 9, depending on if you believe that Hexalectris spicata var. arizonica deserves species status). Hexalectris is a genus of myco-heterotrophic orchids that are generally found in areas with abundant shade and thick, rich leaf litter. In Texas there are three Hexalectris hotspots. One is the mountains of far West Texas, another the shaded canyons and oak/juniper woodlands of the Edward’s Plateau, and the last is the White Rock Escarpment of north-central Texas. The latter is where I sought my targets.

The diversity of Hexalectris in the White Rock Escarpment was only recently discovered, when in the late 1980’s Hexalectris warnockii was discovered at an area nature preserve. Since that time H. nitida, and H. spicata var. arizonica have also been found. In 2005, Hexalectris grandiflora was discovered here as well, marking the first documented occurrence in the United States outside of the Davis and Chisos Mountains of West Texas. It has since been discovered at a few sights in the Edward’s Plateau.

What makes the White Rock Escarpment so attractive to these orchids are the deposits of Austin Chalk. This limestone-rich formation created topography and harbors species of oak and juniper that are more typical of West and Central Texas. It is in the leaf litter under the shade of these species that the orchids grow. The range of these Hexalectris orchids was probably once continuous and more expansive, but climate change over several millennia has pushed them into progressively smaller patches of suitable habitat, where they now exist as relicts of a once broader population.

Hexalectris warnockii

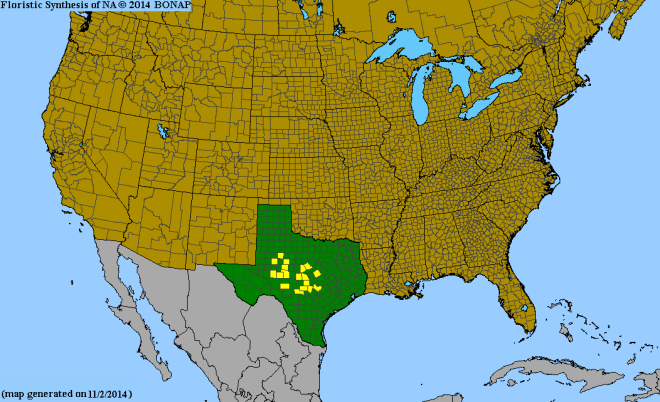

Hexalectris warnockii is one of Texas’s showiest orchids. It is named for Dr. Barton Warnock, a pioneer of Texas botany. He is best known for exploring the flora of the Trans-Pecos, where he discovered many new species and many other species that had never been documented in the United States. Interestingly enough, while Warnock did discover the next species to be highlighted, Hexalectris nitida, he did not discover H. warnockii, which was named in his honor. For more information on this influential figure in Texas natural history, click here.

I had previously observed Hexalectris warnockii growing at the base of some boulders deep in a secluded canyon in the Chisos Mountains. It was truly fascinating to find the same species growing so far apart in conditions that were at the same time different, yet similar. Though H. warnockii has been discovered at several locations since it was initially discovered in the mountains of West Texas, it remains rare and elusive in the state.

Hexalectris warnockii

There is some mystery as to what triggers Hexalectris orchids to bloom. The plants spend most of their life as little more than a rhizome and set of roots, and each individual may only bloom a couple of times each decade. While rainfall is often cited as a trigger for blooming in West Texas, this doesn’t necessarily hold true elsewhere. In the White Rock Escarpment, for example, some years may provide an excellent bloom for one species, and a sparse bloom for others. While H. warnockii seemed to be having a banner year this year, our guide, Gary Spicer, informed us that H. nitida seemed to be showing low numbers.

Fortunately we did find a few. Most of the H. nitida in the Edward’s Plateau and White Rock Escarpment are cleistogamous, meaning that the flowers self-pollinate and thus never open. Gary, who frequents the area, did say that each year he sees a few plants with an open flower or two, but unfortunately we were unable to find any during out visit.

As I mentioned before, H. nitida was discovered by Barton Warnock. He found it while working on his PhD dissertation on the vegetation of the Glass Mountains. H. nitida is also commonly known as the Shining Coralroot due to the reflective sheen it gives off when hit by a stray beam of sun penetrating the canopy.

Hexalectris nitida

Hexalectris has become one of my favorite plant genera. They are both challenging to find and breathtakingly beautiful, and I look forward to continuing to explore Hexalectris habitat in all three of our state’s hot spots.