Black Scoter Drake

I’ve never been one to “chase” birds – that is, to make special trips just to see some vagrant rarity that has appeared in some place significantly outside its normal range – a common occurrence in the Lonestar State. I don’t mean to say that I have an issue with those folks make a habit of chasing birds to add to their life, country, state, or county lists. In fact, it seems like a fun and potentially highly rewarding activity. It’s just not something I’ve personally felt inclined to do. That is, until I heard that a group of Black Scoters (Melanitta americana) that had shown up at lake in a state park less than two hours from our home.

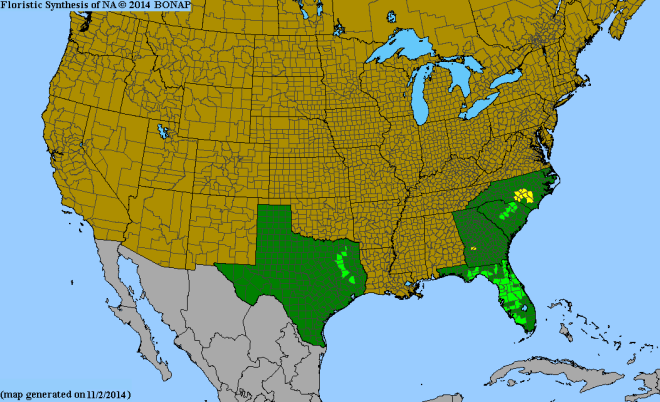

The Black Scoter is an uncommon sea duck that breeds on the arctic tundra in three disjunct populations: one in eastern Canada, one in Alaska and extreme northwestern Canada, and one in eastern Siberia. They winter almost exclusively on the Atlantic Coast of North America and the Pacific Coasts of North America and Asia. Here they show a preference for cold water and rocky shorelines where abundant populations of mollusks, crustaceans, and other aquatic invertebrates occur. They only occasionally turn up in the Gulf off the Texas coast. Observations inland anywhere are generally rare, and virtually unheard of in Texas. That is not to say it doesn’t happen – in 2018 a few were observed in a pond in Austin, and there have been sporadic sightings prior to that – but I must stress, it is a VERY rare occurrence.

A couple weeks ago, however, I saw a post by a Facebook friend with photos of a raft of 18 Black Scoters at Fairfield Lake State Park. What’s more, is that they seemed to be fairly approachable. Given my affinity for waterfowl, and the joy that photographing them brings me, I could not resist the promise of photographing these rarities.

So on Superbowl Sunday I opted out of watching the Big Game, and Carolina and I left the house just before dawn to try our luck at finding the scoters. We had never been to Fairfield Lake State Park, which is nestled in the Post Oak Savannah about an hour and a half south southeast of Dallas.

I really didn’t know what to expect when we arrived. I knew where the scoters had been observed, and I hoped that when we arrived we would see them right away. As is almost always the case, we did not. It was a clear day, and I really hoped to photograph them in the early morning light, before the sun rose too high and her light grew too harsh.

When we pulled into the parking area I did see a small raft of ducks. Hoping it was the scoters I rushed for a closer look, but it turned out to be a group of Ruddy Ducks, their tiny tails sticking straight up. I positioned myself behind a large clump of Phragmites near the last known location of the scoters, and hoped something might turn up. Before long a large raft of American Coots (Fulica americana) appeared. Then a Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) drake arrived, accompanied by a trio of hens. A drake Bufflehead, in my opinion, is one of the most beautiful birds in the country, particularly when the light catches the iridescent plumage of its head. This species is a bit of a “nemesis” for me, at least photographically speaking, as I have yet to capture a good image of one, despite exerting considerable effort. As I watched the drake draw closer through the viewfinder, I began to think that I would finally have my chance. But to my dismay, in a flash, the drake and his hen escort took to the air, as did all other waterbirds in the immediate vicinity. I soon learned the reason why, as I turned around and saw Carolina frantically waving to capture my attention. Apparently a River Otter had just passed less than 50 feet behind me and entered the reeds that I was using to conceal my presence. Despite not getting as close as I hoped, I ended up with my best Bufflehead image to date. We would not see them again that day.

Bufflehead Drake

My attention quickly shifted from waterfowl to semi-aquatic mammals, as I entered the water and scoured the reeds for the otter. The water was frigid, and it felt like tiny ice knives were piercing the skin of my legs, but I quickly put it out of my and continued my search. I could see the reeds moving, and hear the otter fervently sniffing the air. I moved about, circling the entire patch of reeds. In doing so, however, I gave the otter the chance to slip out behind me, and I caught sight of it quickly swimming away. We watched as distant rafts of coots took to the air as the otter swam through them. Knowing their playful nature, I couldn’t help but think that it was deriving some form of satisfaction from this.

American Coots

With the otter gone, the coots soon began to return. I laid on the shoreline and tried to capture a few images of the group. My focus was disrupted when I caught sight of something bouncing in my peripheral vision. It was an American Pipit working the shoreline in search of food. I turned my attention briefly to the little songbird until it left the area.

American Pipit

While I was on my belly with the birds, Carolina was at the picnic table enjoying her Yerba Mate. As I approached, she asked if the bird I was after was black with a black and orange bill. I said that it was, and she pointed to a lone Black Scoter drake a couple hundred yards away by the boat ramp. Excited, I began quickly making my in its direction, until a boat launched and the scoter took off flying clear across the lake. Disheartened, I decided to take a break from the water. We had a snack and enjoyed a flurry of bird activity in the picnic area. Eastern Bluebirds, Ruby-crowned Kinglets, Downy Woodpeckers, Dark-eyed Juncos, Carolina Chickadees, and more bounced around. I tried my luck at photographing an Eastern Phoebe (Sayornis phoebe), but found it difficult to get a clean shot.

Eastern Phoebe

When I first heard about the Scoters I called my mom to see if she’d be interested in joining us in our pursuit. Much to my delight, she and my dad decided to make the trip up from the Houston area to meet us. They arrived mid-morning, just as the Spring Beauties (Claytonia virginica) were beginning to open.

Spring Beauty

We visited for a moment, and then Carolina noticed that the scoters had returned. This time there were six of them. Again I began my approach, but again the birds were disturbed – this time by a canoe. Fortunately this time they only flew a short distance away. I entered the water again, this time getting as deep as my chest. The cold took my breath away, but the day was turning out to be unseasonably warm, which helped a little. In the water I could approach fairly closely but not close enough to get the shots I was after, so I devised a plan. The scoters seemed to be returning to the same area to forage. It was adjacent to a shoreline comprised entirely of softball to baseball sized rocks. Just off shore was a dense layer of woody vegetation. I moved over to the shore and laid down on the rocks half in the water, and hoped that the vegetation would help break up my outline.

It worked, and I watched through my viewfinder as the scoters came in at high speed. They drew closer and closer until they were within 25 feet or so. Then they began to forage comfortably, diving and probing the rocks for prey. At this time it was around 11:30 and the light was quite harsh, but I wanted to make the most of the encounter so continued taking photos until another boat interrupted the scene and the scoters vanished once more.

Black Scoter Drake

Mature (Foreground) and Immature (Background) Black Scoter Drakes

With the birds gone again, and the light conditions worsening, I gave up on photography for a while. We went back to the picnic area to have lunch and visit, and then set out to explore the rest of the park. We were impressed with the facilities, which included a variety of trails and excellent campgrounds. After a couple of hours my parents left and Caro and I visited the entrance station/gift shop. We then went back to the boat ramp in hopes that the scoters had returned.

They were back! By now it was 3 PM, and boat activity had dropped of significantly – presumably because people were getting ready for festivities associated with the Superbowl. I repeated my strategy from the morning, enduring the pain of laying on a bed of uneven rocks. It was miserable, but it paid off, and once again the scoters came in close – at times too close for my camera to focus.

Black Scoter Drake

I found this mid-afternoon light to be the best for photographing these handsome ducks. The bluebird skies were reflected brilliantly in the water, and the bright light bounced off the water’s surface to a degree, and helped to draw out the detail in the drakes’ deep black plumage. They do not appear glossy or matte, but rather an almost metallic jet black, much darker than the coots foraging nearby. The Black Scoter may lack the bright iridescent coloration of many other species of its family, but in my humble opinion the combination of its solid black plumage and bright yellow/orange bill makes it one of our most beautiful ducks.

Black Scoter Drake

Black Scoter Drakes

Black Scoter Drake

Black Scoters

Black Scoter Drake

I spent hours that day laying on the rocky shore. Slowly the sun crept toward the horizon. The quality of light began to improve, at least in the traditional sense. In most other circumstances I would favor this evening light, however in the case of the Black Scoter I found it less preferable than the light earlier in the afternoon. I still took advantage of the last of the available light and captured a few more images before the day’s end.

Black Scoter Drake

Black Scoters

With the sun all but gone, I left the shoreline and went to change into clean, dry clothes. As soon as I left the bathroom I could hear Caro calling for my attention. She had seen the otter again. We spent our final moments in the park following the Mustelid as it patrolled the shoreline. The otter is part of a developing success story for Texas wildlife, as its numbers have been steadily increasing in recent years, and it is slowly repopulating areas where it had been previously extirpated.

On the drive home, at a time when most were probably enjoying the game and its associated commercials, I found myself pondering the Black Scoters. Encountering this species inland in Texas during pre-settlement times would have been virtually impossible. Today they turn up on man-made lakes, reservoirs, and large, deep ponds – features that were created through human alterations to the habitat. The most likely scenario for these birds, in my opinion, is that they were blown off their normal migratory route by some inclement weather, and desperate for rest dropped down to the first large water body they spotted. Hungry and exhausted, they tried their luck at foraging and found the area to be a productive feeding ground. Slowly they began to regain their strength and a few at a time have been departing for familiar territory.

If any of my readers are interested in trying your luck at finding them, I read a report that there were still four remaining as of yesterday. They have been located in the day use area, between the swim beach and the boat ramp at Fairfield Lake State Park, in Freestone County, Texas.