Target Species:

Giant Coralroot (Hexalectris grandiflora)

Mexican Catchfly (Silene laciniata)

Canyon Tree Frog (Hyla arenicolor)

Glorious Scarab (Chrysina gloriosa)

Glorious Scarab

There are those profound moments in life that help shape who we are. Experiences that put things into perspective, and fill us with a sense of purpose and being. Moments that bring clarity to an otherwise murky sea of questions, concerns, and uncertainty. For me most of these moments occur when I’m in the natural world – in places where the advance of civilization and the concrete world is less evident. These wild places are my “church”, for it is here that I seek the direction and advice that guides me, and puts me on my path. Make no mistake, I do not hold any misconceptions that Mother Nature reciprocates my feelings toward her, but rather I take comfort in my insignificance in the grand scheme of the natural cycle. In these moments I know that my life will be fulfilled, for I could never hope to run out of new natural wonders to discover.

One such moment occurred recently in the Davis Mountains of West Texas, when Carolina and I stood high in a narrow canyon overlooking the rain-drenched valley below. We were soaked from head to toe, yet our spirits were not dampened as we pondered the denizens of the forests and meadows that lay below us. On the walk up we had passed groves of massive Ponderosa Pines (Pinus ponderosa), one of the many Rocky Mountain relicts that persist in these sky islands. Among these pines was the largest individual recorded in the state of Texas.

High Elevation Valley with Ponderosa Pine, Texas Madrone, and a variety of oaks

Rain in West Texas is a beautiful thing. You can literally see the world come to life as it rains. You can smell it, hear it, feel it. It’s a difficult sensation to describe. Though in these sky islands, rain is not as scarce as one might think. Sky islands are unique habitats that occur in isolated mountain ranges in the desert southwest. Here warm air cools as it rises up the slopes and moisture accumulates. This combines with annual monsoons that typically begin in July and last into September, soaking the mountains with nearly daily afternoon thunderstorms. The result is annual levels of rainfall that may be 4 times greater or more than the surrounding desert. Temperatures are significantly cooler as well. These conditions result in the presence of several species typical of the Rocky Mountains as well as species of the desert southwest. Couple this with the fact that West Texas and northern Mexico is a a significant center of endemism, and the importance of the Davis Mountains for biodiversity becomes clear.

We were exploring the Davis Mountains Preserve, owned and managed by the Nature Conservancy in Texas. This 33,000 acre preserve protects the highest and most spectacular portion of the Davis Mountains. It joins approximately 70,000 acres of additional land protected through acquisition and private landowner conservation partnerships. The result is the protection of over 100,000 acres of sky island habitat that is critical for a number of rare and declining species and natural communities. Here we observed an array of fascinating plant and animal species typical of these sky islands.

A rain-drenched montane woodland with an overstory of large Ponderosa Pines and an understory of oaks and Texas Madrone

Topping out at over 8,000 feet, the Davis Mountains are the tallest, and largest mountain range confined entirely to the Lonestar State. Though the Guadalupe Mountains are indeed taller and more extensive, we share them with New Mexico. The Davis Mountains were the last refuge for Mexican Gray Wolves and Grizzly Bears in Texas. Those these apex predators are gone, the Mountain Lion still roams here, and Black Bears are making a comeback. Today, the Davis Mountains remain one of the final strongholds in Texas for a variety of plant and animal species. Perhaps the most spectacular of which is the Giant Coralroot (Hexalectris grandiflora).

The rain was just beginning to let up when Carolina spotted them. A clump of pink beacons shining against the wet rocks and grasses. She had found the Giant Coralroot. It is hard for me to describe the sense of wonder and excitement that overcomes me while I observe such an elusive treasure. The clump of orchids had at least 10 stems with dozens of flowers in various stages of development, from bud to senescent blooms. Over the next two days we would end up observing four clumps and a total of approximately 15 plants.

Giant Coralroot

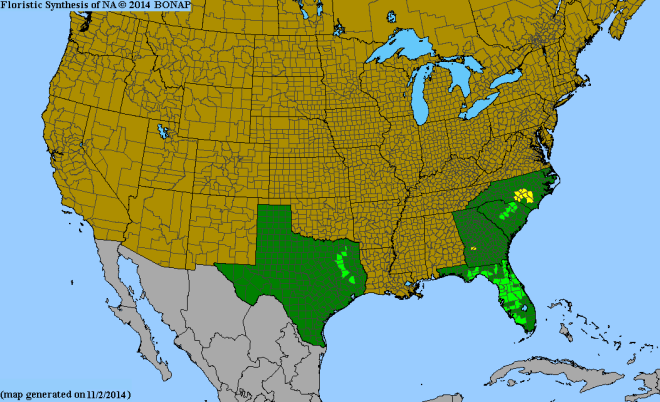

Previously the Giant Coralroot was thought to occur in the United States only in the moist pine-oak-juniper canyons of the Davis Mountains. Though it remains restricted to Texas, it has since been discovered in the Chisos Mountains within Big Bend National Park, the White Rock Escarpment of north-central Texas, and oak-juniper woodlands of the Edward’s Plateau. They seem to be exceedingly rare in these areas, however, and their real stronghold in the U.S. remains the Davis Mountains, where they are relatively common in high elevation forests dominated by Alligator Juniper, Pinyon and Ponderosa Pines, Texas Madrone and a variety of oaks.

Giant Coralroot

Giant Coralroots are myco-heterotrophs, obtaining energy and nutrients from the mycorrhizal fungi of tree roots. Unlike most plants they do not photosynthesize, and therefore do not require chlorophyll-containing leaves. They spend most of their lives as nothing more than an underground rhizome and roots, but following the onset of the summer rains, they begin to send up stalks that may bare a dozen or more bright pink blooms. They seem to bloom sporadically from late June to mid September, likely peaking in mid to late July in most years.

Giant Coralroot

These spectacular orchids are easiest to find growing beneath trees and at the base of rocks where moisture and organic material accumulate, providing ideal conditions for both the plants and the fungi they depend on. Though there is a lot of respectable competition, the combination of their beautiful blooms, interesting life history, and the spectacular places that they inhabit make this my favorite species of orchid.

Giant Coralroot

Giant Coralroot

Growing near the orchids was Mexican Catchfly (Silene laciniata). This striking wildflower occurs in the mountains of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, barely entering Texas in the mountains of the Trans-Pecos. It’s name comes from its sticky stem, which can trap insects in order to protect the plant from predation.

Mexican Catchfly

A number of milkweed species occur in the West Texas sky islands. We observed Asclepias latifolia and Asclepias brachystephana in the lower elevation grasslands. Higher up we came across Asclepias texana, Asclepias subverticillata, and Asclepias engelmanniana in bud. The true star of the high elevation milkweeds was the Nodding Milkweed (Asclepias glaucescens). We found one robust flowering plant growing alongside a rocky stream in a canyon shaded by Alligator Juniper and Pinyon Pine.

This large, showy milkweed is primarily a species of the mountains of Mexico. It barely enters the United States in the sky islands of West Texas, and southern Arizona and New Mexico. In Texas they are restricted to the Davis, Chisos, and Guadalupe Mountains.

Nodding Milkweed

Like Asclepias glaucescens, the U.S. distribution of Threadleaf Phlox (Phlox mesoleuca) is largely restricted to the sky islands of the southwest.

Threadleaf Phlox

In addition to species that are primarily Mexican in their distribution, the Davis Mountains provides refuge for a variety of Rocky Mountain relicts. Purple Geranium (Geranium caespitosum), for example, occurs primarily in Ponderosa Pine savannahs and other coniferous woodlands of the Rockies from Wyoming to northern Mexico.

Purple Geranium

Purple Geranium

The Harebell (Campanula rotundifolia) has an even broader distribution, occuring in the formerly glaciated northern United States and Canada down through the Rocky Mountains, and into the sky islands of the southwestern United States and Canada. It is common in the high elevations of the Davis Mountains and puts on a spectacular show during the summer monsoon.

Harebell

One of the Davis Mountains most spectacular botanical residents is the Desert Savior (Echeveria strictiflora). This succulent member of the stonecrop family (Crassulaceae) is primarily found on rocky canyon walls and slopes of central and northern Mexico. In the United States it is known only from Jeff Davis, Brewster, and Presidio Counties in far West Texas.

Desert Savior

We found several growing from rock crevices and the bases of boulders at elevations above 6000 feet. Here they were able to take advantage of minute amounts of soil and moisture that collect over time. In the Davis Mountains they seem to be found primarily in exposed rock outcrops and canyon walls adjacent to rocky streams.

Desert Savior

The Desert Savior is a truly spectacular plant. It’s stalk of waxy, fiery flowers reaches up to a foot and a half over it’s thick, grayish green succulent leaves. Each curled stalk may bare 2 dozen or more flowers that gradually open, unfurling the stalk as they develop and fade. Hummingbirds are likely an important pollinator of these succulents, as evidenced by their bright red coloration, somewhat tubular flowers, and the fact that their peak blooming seems to coincide with the start of hummingbird migration of late summer.

Desert Savior

Desert Savior

The mountains of Trans-Pecos Texas boast more species of Hexalectris orchids than anywhere else in the country. For some time I had communicated with North Texas botanist Matt White on our shared interests. As luck would have it, while returning to the Davis Mountains Preserve visitor center, our friend, The Nature Conservancy volunteer, and local landowner Gary was talking to a man that he introduced as Matt White. This chance encounter led to Matt guiding us to a population of Texas Coralroots (Hexalectris warnockii) that he had stumbled across on a remote rocky ridge a few hundred meters from the preserve’s main road. He made a comment that caught my attention – that these plants and their ancestors have likely been at this spot for hundreds of years. And in all likelihood we were the first humans to ever see them, and the last that ever will. I smiled at the prospect, and hoped it to be true.

Texas Coralroot

Following a long day of exploring the Davis Mountains Preserve, we decided to spend the evening resting our legs by taking a leisurely drive along the scenic loop that surrounds the range. I use the term resting loosely, for it seemed like every few hundred feet we were stopping to explore some new biological or geological wonder. After a while we passed below Sawtooth Mountain. The mountain is a prominent landmark in the area, its peak reaching nearly 7,700 feet above sea level, and rising nearly 1500 feet above the surrounding slopes.

Like the Davis Mountains Preserve, Sawtooth Mountain and its surrounding habitat is protected by the Nature Conservancy. However the mechanisms that protect the two are quite different. While the Davis Mountains Preserve is owned outright by the conservancy, Sawtooth Mountain remains private, and instead is protected through a conservation easement. Conservation Easements are legally binding documents that place restrictions on land use in order to achieve certain conservation objectives. Sawtooth is another piece of the puzzle that has led to the protection of over 100,000 acres of these sky islands.

Grassland grades into pinyon-juniper-oak woodlands on the slopes of Sawtooth Mountain

Sawtooth Mountain looms over an interest rock outcrop

In addition to their unique flora, the Davis Mountains supports an equally interesting faunal community, melding species of the mountainous west, the desert southwest, and those primarily Mexican in their distribution. In a single day one can hear the call of the Stellar’s Jay alongside that of the Cactus Wren and Painted Redstart. Rare vagrant bird species turn up here, and reptiles like the Greater Short-horned Lizard thrive in one of the few areas of suitable habitat in the state.

The monsoon rains bring with them an increase in amphibian activity. We observed many Red-spotted Toads (Anaxyrus punctatus) during our visit. These large, handsome amphibians occur in a variety of habitats throughout most of the southwest, down into central Mexico.

Red-spotted Toad

One of the most memorable experiences of any trip to the Davis Mountains is hunting for Canyon Tree Frogs (Hyla arenicolor) as they sit perfectly camouflaged among boulders adjacent to pools in high elevation canyon drainages. In Texas the Canyon Tree Frog is restricted to a handful of mountain ranges of the Trans-Pecos. Though most are brown to gray with dark brown blotches, occasionally a striking green or green-spotted individual turns up. Carolina spotted one such animal camouflaged among the lichen on a large boulder.

Canyon Tree Frog

As a child, I remember being captivated with the insect community in West Texas. My parents indulged me as I ran about the desert with a net in hand, eagerly trying to capture and identify the staggering array of flying and crawling six-legged wonders that call the Trans-Pecos home. There are few places in the country that provide as wonderful an entomological playground as West Texas.

One of the most conspicuous members of the insect community is the Arizona Sister (Adelpha eulalia), a member of the brush-footed butterfly family (Nymphalidae). On warm, sunny days that can be seen dancing about the canyon floor and rocky outcrops seeking moisture and areas of mineral deposits. At some such deposits its not uncommon to see dozens of different species sharing the same space in search of essential nutrients that their nectarivorous diet does not provide.

Arizona Sister

The Orthopterans (grasshoppers, katydids, and crickets) of the Trans-Pecos range from species of muted camouflage to those with fitting, gaudy names like the Rainbow Grasshopper. Carolina spotted this blue-winged grasshopper (Trimerotropis sp.) resting among the pebbles in a mountain wash. Though they initially appear to be adorned in dull, muted tones, when they jump they reveal their translucent blue hind wings and cobalt blue markings on the inside of their hindlegs.

Blue-winged Grasshopper

It’s always a treat observing tiger beetles. Ruthless predators, tiger beetles are lightning fast and armed with deadly mandibles. We observed these Western Red-bellied Tiger Beetles (Cicindelidia sedecimpunctata) scurrying about rocks adjacent to a mountain stream. This species, like so many others in the area, barely enters the U.S. in extreme western Texas and southern New Mexico and Arizona.

Western Red-bellied Tiger Beetle

The Western Rhinoceros Beetle (Xyloryctes thestalus) is one of the largest, most abundant beetles of the Davis Mountains. Following the onset of the monsoon they emerge in droves and seek out ash trees (Fraxinus spp.), their primary food source.

Western Rhinoceros Beetle

The real gems of the sky islands, however, are the beetles of the genus Chrysina. There are five species in the United States, two of which occur in Texas. In what I suspect is a common occurrence among lifelong naturalists, I have certain species that I always admired and dreamed of one day seeing while pouring endlessly through field guides and other nature books as a kid. One of these species was the Glorious Scarab (Chrysina gloriosa). It is a species that looks more at home in the tropics, in places well out of reach.

I had looked for this species on many previous trips to the Davis and Chisos Mountains, and had always left having only caught glimpses of elytra discarded by some predator, or some smashed semblance of what once was a Glorious Scarab on busy roads and trails. But on this trip, much to my delight, a lifelong dream was realized when I saw a live Chrysina gloriosa crawling on the ground on our final evening in the mountains. I must have made some strange gleeful sound as I reached down to pick it up. I examined it closely, taking delight in this serendipitous encounter.

Glorious Scarab

Chrysina gloriosa is highly sought after by collectors, and it is easy to see why. Fortunately they remain common in sky islands from Arizona to West Texas. The beetle’s brilliant greens were impossible to capture on “film”, but that didn’t stop me from trying. The elytra (hardened outer wings) of Chrysina gloriosa are decorated with metallic silver streaks that brilliant reflect the light. It is believed that the bright coloration and streaked pattern help break out the outline of the Glorious Scarab when it feeds on the juniper leaves that it depends on, helping to camouflage it from would-be predators. In all we would find five individuals that night and the following morning. It truly was the perfect ending to a spectacular trip that was rich in biodiversity.

Glorious Scarab

The Davis Mountains truly are one of Texas’s natural treasures. We can take comfort knowing that the biodiversity, scenery, and cultural history will be protected for generations to come thanks to the conservation efforts of the Nature Conservancy, Texas Parks and Wildlife, and landowners with a passion for the area. I hope to return many times in the future, in an endless attempt to document but a mere fraction of the beautiful and interesting plants and animals that call this sky island home.