It’s been a year. 2025 has been an emotional rollercoaster. In February 2024 I left a job and team that I really loved for an opportunity with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service where I thought I could make a real impact on the conservation of rare plants, animals, and their habitat. In February of this year I lost that job – not due to poor performance or a bad attitude, but rather in what was labeled as an effort to “reduce the federal work force”. The Department of the Interior and several other federal agencies let go of all of their “probationary employees”, which are employees that had worked for the agency for less than a year (or two years in some cases). No effort was made to evaluate workloads, transitions, or need for those position. It’s like an axe fell and without warning we were severed. I’ve posted about this previously so I won’t dwell on it here, and I avoid politics in my posts. I respect and even admire the difference of opinions that exist in the United States, and think that having this diversity of thought is part of what makes this country great. That said, administrations of either party are fallible and should be held to the highest standard. Things have happened this year that have concerned me more than I’ve ever been concerned in the past, so no matter which party or candidate you support, please pay close attention to what happens in our country and do not be afraid to speak up when something concerns you. We are allowed to disagree and discuss those disagreements, and I wish that those discussions were more civil and productive than the increasingly divisive climate we’ve been living in for many years now. (Rant over!)

I feel incredibly fortunate that what started as one of the most difficult experiences of my life quickly transitioned to one of the most humbling and uplifting. I was overwhelmed by an outpouring of support and job offers which allowed my family and I to breathe a collective sigh of relief – we were going to be ok. The next week my good friend John set up a meeting with him and his boss to discuss opportunities at Ecosystem Planning and Restoration, a private firm focusing on environmental and conservation work across the country. It was a great meeting, and things just felt right. I expressed my interest in joining the EPR team, an offer was made, and within a few weeks I had moved on to a different role, leaving over 10 years in government work for the private sector. It was new territory, and a bit intimidating, but the EPR team immediately accepted me as one of their own, and in the past 10 months I have worked on rewarding projects in amazing places with incredible clients. Superlative perhaps, but it has been a wonderful experience thus far.

Throughout the trials and tribulations this year has presented, my wife and son (and friends and family) have been my rocks. Our little man is three now. What a journey fatherhood has been! Full of rewards, challenges, and all the emotions. Though it is admittedly difficult at times, it just keeps getting better, and I’m so thankful for this goofy ball of energy that dominates so many aspects of my life. Photography, too, has been there for me as it has for the past 20+ years – providing me with nature therapy and serving as a creative outlet. Each year it becomes more and more a part of my identity, and though I didn’t have as many days in the field this year, I did have several quality outings and managed to squeeze in photo time during family outings, work trips, and anywhere else I could.

Below are 25 of my favorite images captured this year presented in chronological order. Most of these have been posted to social media, however there are a few that I’ve yet to share. Please enjoy, and I wish all who read this (and everyone else) a happy and healthy 2026.

Please note that the blog initially shows images brighter and less contrasty than they are. To see the best version of each image, hover your cursor above them for about a second. Also – I apologize for any typos. It takes me a while to put these posts together and by the end I really don’t have any interest in proof reading, so there are bound to be a few errors!

Upside Down Bird

When I was still with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, my office was located a couple of blocks from a nature preserve that had a large intact hardwood stream bottom. I frequently brought my camera to work and wandered the preserve. Usually I could find some interesting plant, pollinator, bird, or other natural subject to photograph. On this day in early February I wandered the woods hoping I might encounter some birds, and was lucky to come across one of my favorites – the White-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis). It is sometimes referred to as the “upside down bird” for its tendency to move downward on the tree trunk, or the “yak-yak bird” for its raucous, nasally call. I captured it in some nice soft light among lovely winter tones.

Happy Feet

In the summer of 2024 I really got into pollinators. It was already too late to observe several species that emerge for a brief period in the spring, so I waited with anticipation for this year’s spring to see if I might be able to photograph some of these vernal wonders. In particular I was hoping to run across the blueberry bee (Habropoda laboriosa), a native bee of woodland habitats in the eastern U.S. and southeastern Canada. It is so named because they show a particular affinity for blueberries, and females prefer to provision their nests with the pollen from blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) flowers to feed their larvae. As the specific epithet laboriosa suggests, they dutifully visit flowers. As a result, they are a significant pollinator of commercial blueberry crops. Though the flowers of blueberry are their favorites, they’re also quite fond of eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis), as evidenced by this photo, and will visit a number of other flower species. I have also observed them on blackberries (Rubus spp.), Carolina laurelcherry (Prunus caroliniana), Carolina jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens), and even the ubiquitous crow poison (Nothoscordum bivalve).

Part of what makes encountering a blueberry bee so special is that they’re only active for a short period in the spring, coinciding with the blooming of native blueberries. In my area I can usually expect to find them throughout most of March and into the first half of April. On the day this image was captured, I visited a large redbud tree bursting with blossoms, and was delighted to observe dozens of blueberry bees eagerly seeking their nectar alongside a number of other native bees and butterflies. My favorite part of this image are the “feet” on the hindlegs, which appear to be dangling along with this beautiful bee as she sips redbud nectar.

Lovely Ladies

In mid May, John and I did some survey work in the Nantahala National Forest in western North Carolina. We were meant to be focusing primarily on salamanders (dream job), but it was impossible to ignore the incredible biodiversity in the area. One of the real show stoppers was the pink lady’s slipper (Cypripedium acaule). I’ve been lucky enough to come across these spectacular orchids a few times in my life, and each time they’ve left an impression. When admiring one in the field, it’s hard to imagine a more impressive flower. This trip we came across several, and enjoyed the company of each one.

Charcoal

The southern Appalachians, which includes western North Carolina, is one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet, and certainly boasts the world’s greatest diversity of salamanders. Those who have followed this blog for some time know that I have a particular affinity for these fascinating amphibians, and I felt like a kid in a candy store exploring crystal clear mountain streams, old growth cove forests, and just about every nook and cranny we came across to see what we might find – and we found a lot. I’m including a few of my favorite images here, but really each and every animal we encountered was special. This is the Southern Appalachian salamander (Plethodon teyahalee). It is a member of the slimy salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) complex. Members of this complex are generally difficult to identify by morphological characteristics alone, and are best separated by range. That said, P. teyahalee is generally characterized as having reduced white spotting and being larger than most other members of the complex.

Moss Dragon

One of the most exciting salamander experiences of the trip was finding several red-legged salamanders (Plethodon shermani). This was a lifer for me, and John and I had a blast exploring their high elevation habitat. It’s amazing just how abundant some of these salamanders can be within range and habitat under the right conditions. P. shermani is a member of the woodland salamander (Plethodon jordani) complex. It is primarily found in higher elevation forests in the Nantahala and Unicoi Mountains of North Carolina. Populations are also present in extreme northern Georgia and southeastern Tennessee.

Smoky Mountain Special

This is the red-cheeked salamander (Plethodon jordani). Also commonly known as the Jordan’s salamander, it’s the nominate species of the Plethodon jordani complex, which currently includes seven species, including the P. shermani above. P. jordani is somewhat of a “poster child” for salamander diversity in the southern Appalachians. It’s famous for its striking appearance, and because nearly its entire range is confined to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Here they can be extremely abundant in the right habitat in rich mid to high elevation forests.

Forest Jewel

The salamanders of the Appalachians come in an incredible array of colors and patterns, and include (in my humble opinion) some of the most beautiful animals on the planet. Perhaps none are as striking as the red salamander (Pseudotriton ruber). This was the only individual we saw, and it was found under a large rock next to a picnic area bathroom. This individual is of the “Blue Ridge” subspecies (P. r. nitidus) and differs from other red salamander species by being slightly smaller, and having no black spotting on the chin and posterior portion of the tail. Though I’ve seen a few red salamanders in the past, this was the first time I captured images I was happy with. What an animal!

Yona

We wrapped up our survey work early on our last day and took the opportunity to head into the nearby Great Smoky Mountains National Park. While driving along Newfound Gap Road we spotted numerous cars slowing down ahead of us. Instinctively, we turned into a pull-out just as we spotted a bear right off the road. As luck would have it, we secured the best vantage point for viewing and photographing the bear, something that almost never happens in such crowded parks. We were close, but the light was harsh, with the early afternoon sun creating bright spots and shadows that made photography nearly impossible. There was however, a patch of ferns and other lush vegetation nearby that was illuminated by dappled light filtering through the canopy. “If the bear would just move there,” I thought, “we might be able to capture something.” Sure enough, after a few moments the foraging bruin made is way to that very spot and I captured an image as sunbeams lit up the bear’s face.

Black bears will always hold a special place in my heart. One of my earliest memories is seeing one on Signal Mountain Road during a family camping to the Tetons. Over the years I’ve had many memorable encounters with these bruins. I remember seeing the dying light of our campfire reflected in one’s eyes as it approached our camp late one evening, and chasing it off with hoots, hollers, and hurled rocks. I’ve surprised a few on the trail only to have them huff and hurry in the opposite direction. Once in Yellowstone my brother and I had one follow us up the trail. I don’t pretend that it had some special interest in us, we were simply in the way of where it wanted to go. We moved off the trail and watched it amble on its way.

Yona is the phonetical spelling spelling of the Cherokee word for black bear. The black bear plays an important role in Cherokee mythology, and is thought to be something of an ancestor.

Lethal Lovers

In early July I was conducting a biodiversity survey at a site in Freestone County. It was hot humid, and like most summer days in east Texas, downright unpleasant. Fortunately there were a few wildflowers in bloom, including several large patches of Pennsylvania smartweed (Persicaria pensylvanica) buzzing with pollinators. Where there are pollinators there are predators. Almost every flower had at least one jagged ambush bug (Phymata sp.), and several had mating pairs. Some were quite camera shy, but this pair allowed my lens quite close.

Subtle Beauty

Some might look at this blister beetle (Epicauta sp.) and see nothing but a disgusting bug, but when I look at it I see something bursting with hidden beauty. From its platinum color to the textures of the fine hairs coating its exoskeleton, this really is a striking creature. I photographed it in a prairie remnant one evening with John after a long day of work south of Fort Worth.

Alligator Alley

This is another image captured after a work day in late July, this time along the upper Texas coast. John and I set out to explore Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge and saw dozens of American Alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). I have to admit I stole the title from this image from John, as he captured a similar frame and dubbed it “Alligator Alley” and I couldn’t imagine a better name. I feel extremely fortunate to work with such a good friend, especially one with so many shared interests. Many of my favorite images this year were made alongside John, and we shared many a celebratory beer to commemorate our experiences afield.

Fairy Dust

To me, bees are about as close to real life fairies as one can get. They’re tiny, graceful fliers that spend their time among the flowers. For the past 10 years, Caro has been developing various native pollinator gardens on our property. These gardens include nearly a hundred species of native flowering plants and have attracted hundreds of species of pollinators and predators. Among these we have recorded dozens of species of native bees. Each year is a bit different, with species and their relative abundances changing over time. This year we had an influx of carpenter-mimic leafcutter bees (Megachile xylocopoides). Females, like the one copied here, bear a striking resemblance to female southern carpenter bees, and a number of other Xylocopa species that have primarily black females. Their coloration and body shape is quite similar, however M. xylocopoides are easy to identify, as like other females collect pollen on specialized hairs on their “bellies”, a process that can be seen in this photo (fairy dust!). True carpenter bees are members of the family Apidae and collect pollen on their hind legs.

I did some research to see if this species is truly a mimic of carpenter bees, and could find no resources that presented evidence to that effect. Carpenter bees may be a bit larger and more active, and more readily trigger a fear response (from humans at least), but are no more “dangerous” to potential predators than these leafcutter bees. Perhaps there is some type of mimicry going on here, or perhaps not. If anyone has any specific knowledge on this topic I’d love to hear it!

Shiner Soirée

I’ve already expressed my gratitude toward my friend John for helping me in my career path, but I also have thank him for getting me into fish. I’ve always been fascinated with biodiversity, and have spent considerable time learning about the natural history of various groups of organisms, but until this year I’ve never been particularly excited about fish. Perhaps this is because they’ve always been out of reach of my lens, and photography plays such a big part of my time in nature. This year, however, my family met up with John and his son to explore an east Texas creek and we turned up several small fish that John placed into a small tank. It sparked an idea in me (which has always been in the back of my mind) to try and create naturalistic images using a small tank. I started experimenting, taking substrate from where we found various fish and setting up the tank and photographing the fish as they passed next to the glass. So far I’ve been very happy with the results, and it’s been a lot of fun exploring this new pursuit.

Fast forward a few weeks, and John and I were in the field again. I set up the tank and we ran a sein over a gravel bar in an east Texas stream and captured several small species, including the two shiners seen here. The drabber fish on the left is a Sabine shiner (Miniellus [Notropis] sabinae), a species of greatest conservation need in Texas. They can be found in the eastern portion of the state, from the San Jacinto River Basin east, as well as Louisiana and portions of Missouri and Arkansas. The fish on the right is a red shiner (Cyprinella lutrensis), a widespread species that ranges across the central U.S., including most of Texas. They have also been introduced in waterbodies across the country, and have become a nuisance in some areas outside their native range. This image really doesn’t do the species justice, as the males are incredibly beautiful in their breeding colors.

Splashy

When it comes to fish, it’s hard to top the beauty of the longear sunfish (Lepomis megalotis) complex. This is a plains longer sunfish (Lepomis aquilensis), which was recently split along with a number of other lineages from L. megalotis. I love everything about this fish, from their interesting shape to their incredible colors. They’re also surprisingly fun to catch. I caught this individual while fishing with a worm and a hook in the creek a block from our house. So far I’ve caught five species of native Lepomis here. The creek is really pretty, with a mature riparian buffer and a bottom of sand, cobble, and petrified wood. It contains several deep holes, and even alligator snapping turtles have been observed in it.

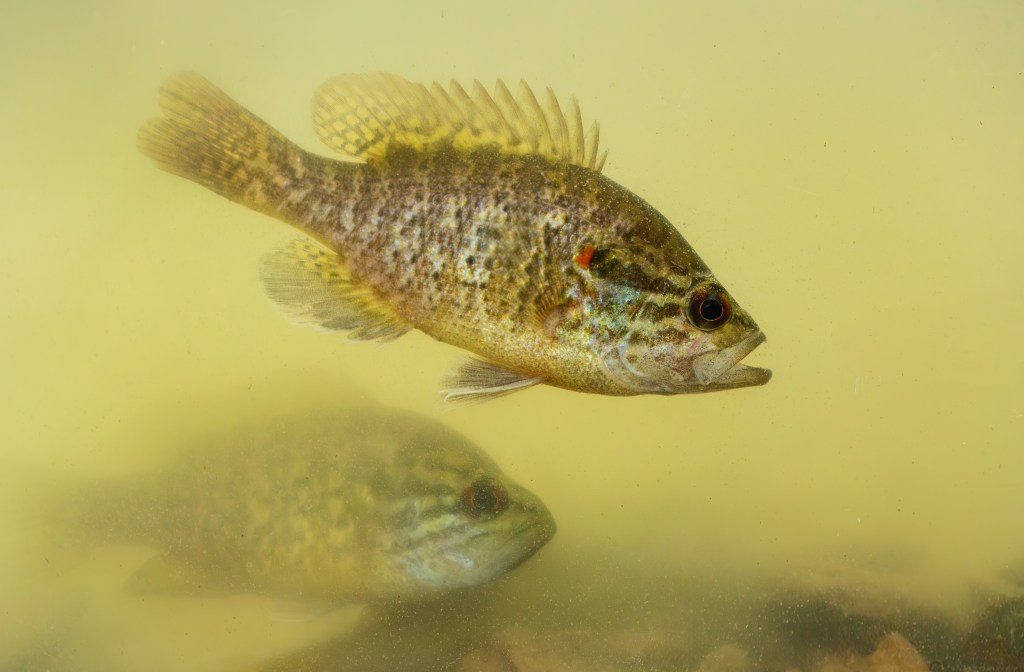

Ready for War

The warmouth (Lepomis gulosus) is another species of Lepomis sunfish native to my area. It almost more bass-like, with a large mouth and more streamlined body. Warmouths are ambush predators and often inhabit murky waters where they hang out among woody debris and undercut banks. These were found in a small tributary of the Angelina River in Nacogdoches County.

River Monster

In mid September I returned to North Carolina for another round of salamander surveys. They weren’t as abundant or diverse as they were during May, but I did manage to turn up a few cool things, including this huge Nantahala black-bellied salamander (Desmognathus amphileucus). These are among the largest of all Desmognathus salamanders, and were recently split along with several other lineages from Desmognathus quadramaculatus. This was one of the more conspicuous, commonly encountered species during both survey efforts, however large adults are quite difficult to capture. Large adults can reach seven inches or more in length and this one was approaching that size. It was found under a large rock directly adjacent to a mountain stream.

Boss Fish

We didn’t do too much traveling as a family this year, however we did manage to get away for a few long weekends. In early October we traveled to the western edge of the Edwards Plateau to explore the upper reaches of the Nueces River. This is an incredibly beautiful section of river with crystal clear, cool water flowing swiftly over rocky streambeds with a backdrop of steep bluffs and cliff faces.

Though the goal of the trip was to spend some time exploring and relaxing in a beautiful part of the state, I did have a few target species in mind. At the top of the list was the Texas, or Rio Grande cichlid (Herichthys cyanoguttatus). This exotic looking fish is the only cichlid species native to the U.S. It’s native range includes the Rio Grande Basin, and “possibly” the Nueces River Basin. I say “possibly” because the literature varies on this. Some resources cite it as being native to the Nueces Basin while others suggest it is likely introduced here. I did a deep dive into this and as far as I can tell, the ambiguity is due to a couple of fish surveys conducted on the Nueces ~100 years ago. A survey conducted in the late 1800s on the Nueces did not detect the species. They were detected in another survey conducted in the 1930s, which was after stocking efforts began. That said, the 1930s survey detected an additional 40 fish species that were not detected in the original survey, the vast majority of which were not species that are stocked.

Personally I think that it makes sense that they would be native to the Nueces, as the Nueces and Rio Grande drainages start to mingle as they approach the coast, and the upper Nueces comes very close to the Rio Grande in west-central Texas, and the habitat of the upper Nueces is quite similar to adjacent portions of the Rio Grande drainage. That said, so many fish species have been stocked, introduced, and re-introduced that it poses challenges in determining native ranges, even within native basins. Whether they are native here or not, it was a treat getting to see and photograph these fascinating fish.

Marbled Salamander Tableau

The marbled salamander (Ambystoma opacum) is perhaps my favorite harbinger of autumn. Each year I put in the effort to find a few. This year we experienced heavy rains associated with a cold front in late October that fell the night before we planned to meet my parents at a pumpkin patch that was located halfway between us. I left early with the family so we could stop at some of my favorite marbled salamander breeding ponds. With my son on my back we explored the pond and within a few minutes had turned up eight salamanders! It was an exciting experience enjoyed by all. My boy even helped me capture some images (or rather climbed all over me and tried pushing every button on my camera).

Marbled salamanders emerge to breed en masse following cool fall rains. Unlike most congeners which breed in water, marbleds court and breed on dry land, and the females lay her eggs under debris in the dry basins of ephemeral wetlands. They then guard the eggs until the wetlands eventually fill with water, allowing the larvae to emerge. The two individuals with brighter patterns in this image are males. Males typically have brighter dorsal maculations, though in our area they seem to be subdued. This image may be a bit too “set up” for some, however When I spotted the fallen cypress leaves and arranged the salamanders on the forest floor, it just looked like art to me. Beautiful creatures in a beautiful setting.

Fallbeast

In early November we took a family trip to Arkansas, where we stayed in a great AirBNB near the town of Hot Springs and spent a few days surrounding the Ouachita Mountains. On our second day my wife enjoyed a morning at one of the world famous spas in Hot Springs, taking in the water from the areas natural springs. My son and I went out for a hike in the nearby mountains. I had salamanders on the mind, and we were lucky enough to turn up a couple of these beautiful western slimy salamanders (Plethodon albagula). As with the marbled salamander image above, my three-year old “helped” me capture this image. By “help”, I mean climbed all over me, gathered an inordinate amount of leaves, and found plenty of dirt for the salamander to “eat”. Herping and photographing with a three year old certainly has its challenges and frustrations, but its such a rewarding experience, and it brings me a lot of joy seeing my son enjoy nature and these creatures that I cherish.

Golden Mirror

On a very cold and windy day in Arkansas, we visited the Little Missouri River where it cuts through the Caddo Mountains. This scene caught my eye, with the boulders in deep shade and the water reflecting the autumn leaves of hardwoods surrounding a small gorge. The shade rendered the rocks quite cool, and I opted not to warm them. It was a very cold day and the clash of warm and cool here makes me think of having cold skin but a warm heart while exploring this little slice of the Ouachitas.

Mind Blowing

Immediately following our Arkansas trip I headed south to the coastal bend of Texas with John for work. By day we were surveying rare plants in coastal prairie remnants, and in the evening we were exploring the fish diversity of the Gulf. We wandered along a jetty near our accommodations and I was blown away by the diversity of fish we encountered. Perhaps the most striking was this little stretchjaw blenny (Chasmodes longimaxilla). It’s a species I had never seen or even heard of prior to that day, but I was blown away by its beauty. It’s one of the things that excites me most about biodiversity is that there is and will always be some fascinating new organism to discover. Even after 40 years of exploring the natural world, I am still amazed on a regular basis.

Sea Monster

While exploring the jetty, we observed several Gulf toadfish (Obsanus beta) among the riprap and clumps of oyster shells. What a creature! They look like some deep sea monster, and without scale it’s easy to picture them as some sort of ship consuming leviathan. We captured a few and I photographed this one in a tank with a little bit of flash to highlight its mysterious, nocturnal nature.

Phoenix

In November and December I took a couple of camping trips to my favorite deer photography location with my dear buddy James. We spotted this stunning buck right off the road on a warm November morning. I may have uttered an expletive or two in disbelief as I slammed on the brakes. Before I could raise my camera he was gone. Shortly after, however, we spotted him again and decided to pursue him on foot. We were treated to an incredible show of rut behaviors as he checked out a group of does, ran off a few lesser bucks, and sought the trail of potential mates. Though we had a front row seat to the action, the light was already harsh and the setting was very cluttered. We followed him for a while, as he seemed generally unconcerned with our presence. For a split second he stopped at the edge of a small clearing. He was mostly in shadow, but the sun lit up the foreground grasses and a post oak dressed in autumn foliage in the background.

Paragon

I captured this image on the last day of our December trip. Photographing this beautiful buck was a special experience for a number of reasons. He’s a beautiful animal, with a rich color to his coat and beautiful chocolate antlers with polished tips. We first saw him the morning prior and he quickly became the number one target of the trip. We crossed paths several times that day. He was tending a doe that hadn’t been bred during the peak of rut in November, and though he was hesitant to leave her side, he never strayed from heavy cover, and any attempt we made to approach resulted in a flash of white and the crunching of leaves as he bounded away. He never strayed too far from the doe, however, and we repeated this process several times until the light ran out.

The next morning dawned to the aftermath of a frigid cold front that moved in overnight. We decided we were going to try again, and made our way to where we had seen him the previous night. On our first pass we were met with a few does, but there were no antlers to be seen. We scoped out a few other areas to no avail and then backtracked to where we thought he might be. And just like that, there he was, standing like a statue in the timber mere yards away. There he remained, just behind the object of his affection as we photographed him in multiple poses in a beautiful setting. It was one of those surreal moments that felt like a dream, especially with how spooky he had been the prior day.

An already incredible experience was made even more special by sharing it with one of my closest friends. We spent the weekend camping and shared good food, comradery, and made memories to last a lifetime. That’s one of the things I love most about photography – I need but look at an image like this for all of those memories to come flooding back.

Water Dragon

At the end of December my family and I met up with John, his son, and some other good friends to look for Gulf Coast waterdogs (Necturus beyeri). John had set out traps the day prior and had just checked them when we arrived. The fourteen traps yielded this lone adult waterdog. What an animal. I have seen these numerous times in the past, but this is the first time I really took the time to admire them up close. They have a beautiful purplish skin color with numerous small and large black and brassy spots, and those external gills are magnificent. This is a fully aquatic salamander species that can be found in drainages of the western and central Gulf. It has been undergoing some taxonomic revision in recent years, and some suggest that there are additional cryptic species within the complex to be described. In Texas they inhabit a variety of waterbodies in the eastern quarter of the state, and hang out in leaf packs, woody debris, and other cover on the stream bottom.