Longleaf Pine Savannah

Before I post a May recap, I wanted to pay tribute to one of our countries most unique and biodiverse communities, the Longleaf Pine savannah. Over the past few years I have been slowly working on a manuscript for a book about East Texas. This post contains an excerpt of that manuscript and some photos that I intend to include in the book.

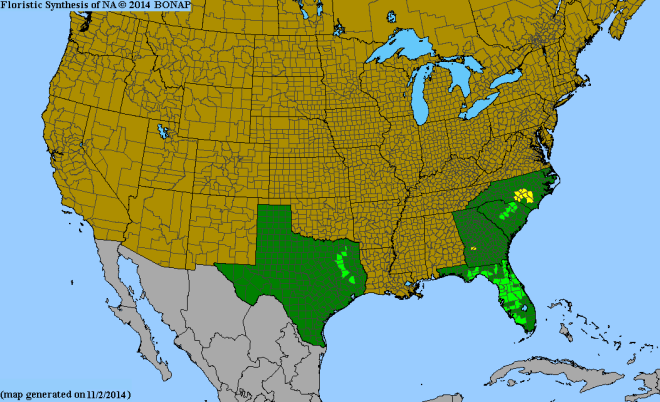

Perhaps no tree better represents the Pineywoods than the longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), both in its historic influence over the landscape and its eventual plight. It most often made its presence known in extensive savannahs, where widely scattered individuals might have lived to be 500 years old, reaching diameters pushing four feet, and stretching well over a hundred feet toward the sky. Once ranging across the southeast, from Virginia to East Texas, the king of the southern pines has been reduced to less than 5% of its native range, and has disappeared across the vast majority of its range in Texas.

Longleaf Pine Savannah with Little Bluestem

Remnants of the fire-loving conifer and the habitats it defines can still be found, however. In the northern part of its range in Texas, which includes Sabine, San Augustine, Angelina, and northern Jasper and Newton Counties, it primarily occurs in rolling uplands. In areas that are managed with regular prescribed fires, one catch a glimpse of the great longleaf pine savannahs of the past. These were perhaps the most biodiverse communities in the southeast; a unique area where prairie and forest mingled.

Occurring on sands of moderate depth, these sprawling forests are kept free of woody understory encroachment by regular fires. The fire-tolerant longleaf pine thrives in the face of the flames, while most other species die out. However, on occasion hardwoods such as blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica), Southern red oak (Quercus falcata), Post oak (Quercus stellata), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), farkleberry (Vaccineum arboreum), and sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua). In the absence of fire American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) and yaupon (Ilex vomitoria) may become invasive.

An ancient Post Oak has survived decades of regular fires in this Longleaf Pine Savannah.

The real show, however occurs on the savannah floor, where hundreds of species of grasses and forbs complete these spectacular ecosystems. Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) is an important component in East Texas, and often occurs in the company of other grasses such as Eastern gamagrass (Tripsacum dactyloides), Pineywoods dropssed (Sprobolus junceus), and wiregrass (Aristida palustris). Brackenfern (Pteridium aquilinum) often carpets the ground and xeric (drought loving) species like Louisiana yucca (Yucca louisianensis) and Eastern prickly pear (Opuntia humifusa) take advantage of the droughty conditions created by pockets of deeper sand. Forbs typical of this community include goat’s rue (Tephrosia virginiana and Tephrosia onobrynchoides), Carolina false vervain (Verbena carnea), Pickering’s dawnflower (Stylisma pickeringii), Carolina Larkspur (Delphinium caroliniana), Sanguine’s purple coneflower (Echinacea sanguinea), soft green eyes (Berlandiera pumila), racemed milkwort (Polygala polygama), propeller flower (Alophia drummondii), butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), clasping milkweed (Asclepias amplexicaulis), pineland milkweed (Asclepias obovata), birdfoot violet (Viola pedata), and false dragonhead (Physostegia digitalis). A number of species that are rare and declining in East Texas occur here as well, including leadplant (Amorpha canescens) and incised groovebar. The range-restricted scarlet catchfly (Silene subciliata) is endemic to the Pineywoods of eastern Texas and western Louisiana.

Scarlet Catchfly blooming in a Longleaf Pine Savannah

These savannahs also harbor a unique, and declining fauna. In fact, some species are so closely tied to this community that they are unable to adapt in its absence. Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis) and Louisiana Pine Snake are in such peril that they have been afforded protection under the Endangered Species Act. Eastern Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) and Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginiana) favor the dense, rich herbaceous layer beneath the longleafs, where bunch grasses provide ideal cover and high species diversity of grasses and forbs results in a bounty of insects. Both species have become rare in East Texas, however efforts to reintroduce the wild turkey have been met with some success.

Other species such as the Bachman’s Sparrow (Peucaea aestivalis), Brown-headed Nuthatch (Sitta pusilla), Northern Scarlet Snake (Cemophora coccinea), and Southern Coal Skink (Plestiodon anthracinus) are on the decline. Species such as the Eastern Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum) and Eastern Fence Lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) remain common, perhaps due to their adaptability. The Tan Racer (Coluber constrictor etheridgei) is a race of racer that is also confined primarily to this community. Surprisingly, even amphibians can eek out a living in these sandy environments. Explosive breeders like the Hurter’s Spadefoot (Scaphiopus hurteri) and Mole Salamander (Ambystoma talpoideum) live the majority of their live deep underground, emerging during significant rains to breed in areas that can hold water long enough for their larvae to develop.

Northern Scarlet Snake

The downfall of the longleaf pine savannah began with the arrival of European settlers to the region. Longleaf lumber was of a superior quality. Rot resistant, and straight as an arrow, it was utilized heavily for the masts of ships. As it began to rapidly disappear, those tending to the forest’s regeneration noted that due to its unique ecology longleaf took a very long time to grow to a size suitable for harvest. So instead of replanting them, they opted for species like loblolly (Pinus taeda) and the non-native slash pine (Pinus elliottii), that, though the quality of their wood was inferior, grew much faster and could yield a marketable stand in less time. At the same time a culture of fire suppression was arising. The Europeans did not see fire as a useful tool, as did the Native Americans before them, but rather as a threat to their livelihood. As a result they took steps to eliminate fire from the landscape, and in doing so woody shrubs eventually filled in the open grass-dominated savannahs.

Sun sets in a Longleaf Pine Savannah

The following are a variety of photos of the longleaf pine savannah and its flora and fauna.

Longleaf Pine Savannah

Longleaf Pine seedling

Louisiana Yucca blooms in a Longleaf Pine Savannah.

Longleaf Pine Savannah

Slender Glass Lizard (Ophisaurus attenuatus)

Birdfoot Violet

Ox Beetle (Strategus antaeus)

Eastern Lubber Grasshopper (Romalea microptera)

Six-lined Racerunner (Aspidoscelis sexlineata)

Southern Coal Skink

Hurter’s Spadefoot Toad

Soft Green Eyes

Eastern Coachwhip

Zebra Swallowtail (Protographium marcellus)

Clasping Milkweed

Wrinkled Festive Tiger Beetle (Cicindela scutellaris rugata)

Racemed Milkwort

Sanguine’s Purple Coneflower

Carolina Larkspur

Eastern Gammagrass

Leadplant

Prairie Kingsnake (Lampropeltis calligaster)

False Dragonhead

Texas Red-headed Centipede (Scolopendra heros)

Texas Dutchman’s Pipe (Aristolochia reticulata)

Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus philenor)

Butterfly Weed and Bracken Fern

Pineland Milkweed

Carolina False Vervain

Texas Brown Tarantula (Aphonopelma hentzi)

Slowinski’s Corn Snake (Pantherophis slowinski)

Eastern Fence Lizard

Netleaf Leather Flower (Clematis reticulata)

Propeller Flower