Peyote

Spring in the Tamaulipan Thornscrub is a beautiful, albeit deceiving thing. When the chaparro, huisachillo, and guayacan bloom above a carpet of wildflowers, its easy to forget just what a harsh, unforgiving land this can be. I was bleeding through my jeans when I sat a moment to rest in the shade of a mesquite tree. I don’t think that Carolina, James, or Erin had fared much better. Despite being early March, it was pushing 90 degrees, and the sun was beating down. After taking a long draw from my water bottle, I got up and continued my search. I winced as I pushed through the allthorn, and felt the tasajillo spines pierce my skin. It’s safe to say at that point my spirits weren’t at their highest. But then I heard the voice of my wife as she called out, “I found one, with a flower!” In that moment, pain seemed like an insignificant consideration as I pushed through the tangle of thorns that lay between me and my succulent quarry. I saw Carolina squatting down looking at the base of a large shrub. There, under the shade and protection of a condalia I could see the iconic Peyote in bloom.

Despite being very un-cactus like, the Peyote may be the famous of all cacti. Once fairly common in parts of south and west Texas, decades of over-harvest, poaching, and habitat loss of significantly reduced the populations to the point that today they are a rare sight among the thornscrub. The reason that it has been so persecuted is the psychoactive compound mescaline contained within its flesh.

In fact, Peyote is one of the most well known psychoactive plants. It has been utilized for centuries by native peoples for both its medicinal and hallucinogenic effects. Today Peyote is a controlled substance in the United States due to its use as a recreational drug. It is, however, legal for many native tribes to harvest and consume for ritualistic purposes. And though it may be illegal to harvest or possess, poachers continue to devastate Peyote populations to sell them on the black market.

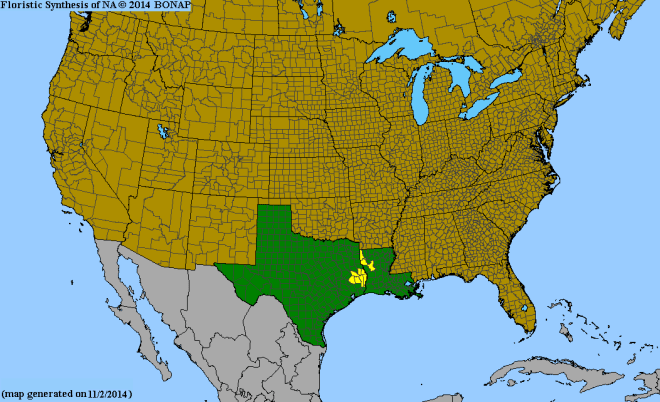

In the United States Peyote is known only from extreme southern and western Texas. Here it occurs in desert scrub and arid brushland, typically growing beneath dense shrubs. It is one of three spineless cacti in Texas. We were lucky enough to observe some in bloom on an extensive private ranch in the Tamaulipan Thornscrub of South Texas, with the help of our dear friends Toby Hibbits and Connor Adams.

Peyote

In our pursuit of Peyote we observed several other species growing beneath the shelter of their nurse plants. We seemed to catch the Heyder’s Pincushion Cactus (Mammillaria heyderi) in full bloom. This small cactus grows low to the ground, and like many species with this growth habit, is very difficult to spot when not in bloom. In the early spring a single plant may put on a dozen or more flowers, generally organized in a ring along the top of the cactus. It occurs from Mexico through south and central Texas west across eastern and southern New Mexico into southern Arizona.

Heyder’s Pincushion Cactus

Heyder’s Pincushion Cactus

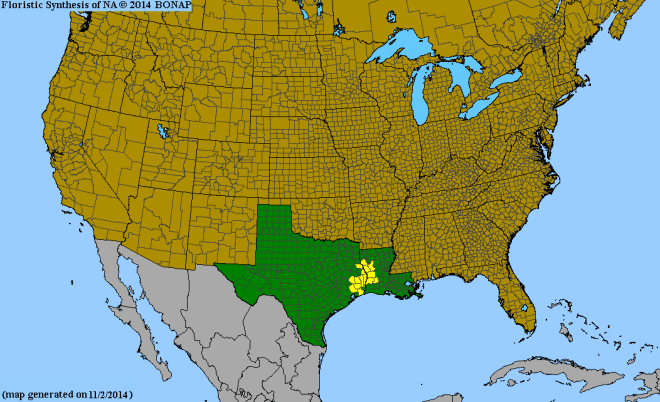

While the Heyder’s Pincushion Cactus may be difficult to spot when not in bloom, the Hair-covered Cactus (Mammillaria prolifera) is difficult to spot even when in flower. This species is tiny, with individual stems not much larger than an egg, though they may occasionally form large clumps. The Hair-covered Cactus is known in the United States only from Texas, where it occurs in only a handful of counties in southern and south-central Texas, most of them along the Rio Grande.

Hair-covered Cactus

Though it is superficially similar to the Mammillaria prolifera, the Runyon’s Pincushion Cactus (Coryphantha pottsiana) is easily differentiate when in flower. Like many species of cactus, the taxonomy for Coryphantha pottsiana is a bit cloudy. It has variably been known as Coryphantha robertii, Mammillaria robertii, Mammillaria bella, Escobaria bella, Escobaria runyonii, and Escobaria emskoetteriana. Some authorities still use the latter, though Coryphantha pottsiana seems to be more widely accepted. The Runyon’s Pincushion Cactus is known from northern Mexico and a few Texas Counties along the Rio Grande, where it is generally uncommon.

Runyon’s Pincushion Cactus

While the previous cacti are generally small, the Horse Crippler (Echinocactus texensis) can reach much larger proportions. While most seem to be about the size of a basketball, we saw some that were easily 3 or 4 times as large. They tend to occur in looser soil including sandy alluvium. They are also frequently found growing in the open, away from nurse plants, though its likely that many plants get their start in the less hostile microclimate of a nurse plant. Their impressive spines seem to be an effective deterrent against mammalian predators.

Horse Crippler

Horse Crippler

Among the most beautiful of all cacti are the hedgehog cacti of the genus Echinocereus, a few of which are endemic to the Tamaulipan Thornscrub of South Texas and northern Mexico. This year our trip coincided with the peak bloom of Echinocereus fitchii, the Fitch’s Hedgehog Cactus. Though they are generally hard to find, in the right habitat they can be abundant, and we saw dozens, blazing the thornscrub with their pink blooms. Like Coryphantha pottsiana and so many other cactus taxa, the taxonomy of Echinocereus fitchii is murky at best. It is considered by many to be a subspecies of the more broadly distributed Echinocereus reichenbachii. For anyone interested in the topic I strongly recommend reading “A hard-to-manage taxon: The Black Lace Cactus (Echinocereus fitchii ssp. albertii)“. Though it discusses the Fitch’s Hedgehog Cactus’s Federally Endangered cousin, it includes a good discussion on the taxonomy of E. fitchii and E. reichenbachii, including characteristics used to distinguish the two.

Fitch’s Hedgehog Cactus

Fitch’s Hedgehog Cactus

In my opinion, the Lady Finger Cactus (Echinocereus pentalophus) is perhaps the most spectacular cactus native to the United States. Confined to northern Mexico and extreme southern Texas, they can form huge mats under the shade of mesquite and other trees and large shrubs. They have even been found growing upon protected ridges adjacent to the Laguna Madre. Their bright blooms shine neon pink under the midday sun.

Lady Finger Cactus

Lady Finger Cactus

The bizarre Pencil Cactus (Echinocereus pentalophus) seems less a cactus and more a tangle of dried branches resting at the base of some thorny shrub. That is, until it’s giant pink blooms open in the early spring and betray its presence to the world. Unlike most other members of its genus, the Pencil Cactus produces a massive tuberous roots that aid in water storage.

Pencil Cactus

The highlight our South Texas cactus hunt, however, was finding the Federally Endangered Star Cactus (Astrophytum asterias) in peak bloom, an experience which I will share in my next blog post.

Star Cactus