Target Species: Purple Bladderwort (Utricularia purpurea)

Purple Bladderwort

This is one I have wanted to see for a long time. Utricularia purpurea is an aquatic, carnivorous plant that inhabits much of the Eastern United States. It barely enters Texas in the extreme southeast portion of the state, where it is rare. I suspect that very few people have seen the Purple Bladderwort here, as the few known populations are not particularly easy to access. Pursuing the photographs seen here was a true adventure, and the highlight of my 2017 quest for biodiversity thus far.

Purple Bladderwort

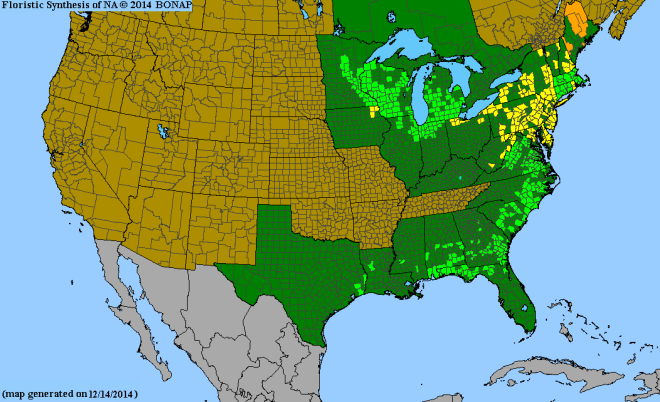

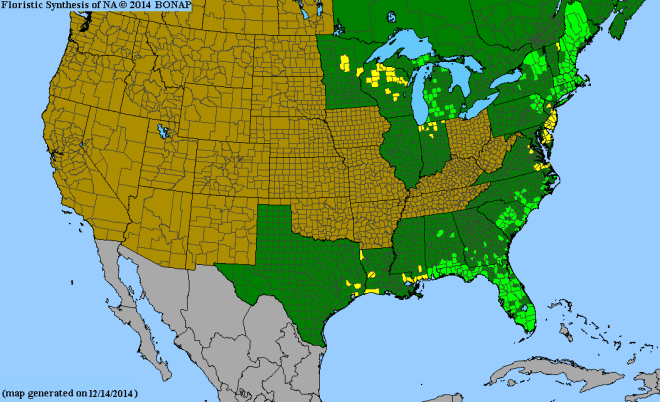

The Purple Bladderwort has a peculiar distribution, not unlike that of another species on my 2017 list, the Blue Lupine. In the case of the bladderwort I suspect that its distribution can somewhat be explained by the presence of appropriate wetlands in the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains, and in glacially formed depressions in the Northeast and Great Lakes regions.

County-level distribution of Utricularia purpurea from http://www.bonap.org. Yellow counties indicate that the species is present but rare.

To see this rarity, I once again called on the good people of the Nature Conservancy of Texas. Wendy Ledbetter, Forest Project Manager, told me that U. purpurea had been reported from a series of flatwood ponds on one of the properties they protect. It was, in fact, very close to where I photographed Streptanthus hyacinthoides a few weeks ago. She was kind enough to take time from her busy schedule to meet me one morning and show me the areas where it had been reported. She brought me to two spectacular flatwoods ponds. We were unsure if any of the elusive carnivores would be in bloom, but sure enough, after minimal effort I spotted one, then another, then another.

Purple Bladderwort

After showing me around for a couple of hours in the morning, Wendy had to leave to tend to other engagements. I thanked her profusely, both for her time and consideration, and for the fine work that she and her colleagues at the Nature Conservancy have done to protect so much our great state’s incredible biodiversity. After Wendy left I returned to the ponds to try to capture some unique images of this spectacular little plant. I was trudging through water that was mostly between 1 and 3 feet deep. To capture some of these images I had to sit, kneel, or completely submerge myself in the water, with just my hands and camera above the surface.

Purple Bladderwort

As previously mentioned, and eluded to in the title, Utricularia purpurea is a carnivorous plant. It contains intricate leaves that float just below the water’s surface. These leaves are loaded with small air-filled bladders that help keep the plant afloat. Each bladder is equipped with a small, hair-like trigger. As tiny aquatic organisms swim by and brush against the trigger, the bladders instantly open, and as the water rushes in to occupy the vacant airspace, the organisms are sucked in. The bladder then snaps shut, trapping them inside where they are slowly digested. In the late spring through the summer the lavender flowers emerge from the depths. U. purpurea is one of several species of Utricularia in Texas, but it is the only one with purple blooms. The others are all yellow.

Purple Bladderwort. If you look closely you can see some of the round bladders under the water.

The flatwood ponds in which I photographed the Purple Bladderwort that day were the finest I have ever seen. These unique aquatic communities occur in clay-bottomed depressions where over the millennia water and organic material have accumulated. Historically they were dominated by a variety of grasses and sedges, kept free from woody encroachment by regular wildfires. In the modern era of development and fire suppression, however, high quality examples have all but disappeared. They have persisted on this Nature Conservancy property, however, as a result of their excellent stewardship which includes frequent burns that penetrate into the ponds. Scattered trees, mostly Swamp Tupelo (Nyssa biflora) exist on the margins, but the centers of the pond are open for acres.

Unfortunately I did not take any photos looking toward the center of the ponds, however I did capture the photo below looking back to the margins. I found U. purpurea to be most common among the grasses and trees along the ponds’ margins.

Flatwoods pond margin

I spent what must have been at least 15-20 minutes lying on my belly, almost completely submerged in the water in order to get a low angle on a particularly attractive grouping of Purple Bladderworts. After finishing I began to retrace my steps out of the pond. As I did, I noticed something that was not there on my way in. There was an 8-9 foot alligator laying on the bottom not 20 feet from where I was laying. I suspect that its sudden presence was a coincidence, and that it hadn’t been slowly stalking me, but none-the-less it gave my heart a good jump. Fortunately the water was shallow and clear, giving me a clear view of the magnificent creature, otherwise I was likely to have stepped on it. I slowly made my way around it, and it never moved. Though somewhat difficult to see, you can make out its head and part of its back in the photo below.

American Alligator

The Purple Bladderwort shared its ponds with its cousin, the Humped Bladderwort (Utricularia gibba). Like Utricularia purpurea, it also relies on the bladders of its submerged leaves to obtain nutrients from animal prey.

Humped Bladderwort

There were several other interesting aquatic species in the flatwoods ponds, but the Floatinghearts (Nymphoides aquatica) really stood out. It is also commonly known as the Banana Plant for its banana-shaped roots.

Floatingheart

Floatingheart

The flatwoods ponds were surrounded by a spectacular series of xeric sandhills occurring on ancient sand deposited by rivers as they changed course over time. I spent some time exploring these beautiful communities, where I found a number of Eastern Prickly Pears in bloom.

Eastern Prickly Pear blooms in a xeric sandhill

Eastern Prickly Pear blooms in a xeric sandhill

I also took a moment to photograph the Pickering’s Dawnflower (Stylisma pickeringii), another species typical of deep sands, as it bloomed among the cacti.

Pickering’s Dawnflower

As if all of the above wasn’t enough, in the morning Wendy and I observed this Eastern Hognose Snake (Heterodon platirhinos) up to its anti-predator high jinks. It spread the ribs of the anterior portion of its body creating a hood-like effect similar to that of a cobra. This behavior has earned it the colloquial name of “spreading adder”. Occasionally it would feign a strike, but never attempted to actually bite me. Eastern Hognose Snakes feed primarily on toads, and have specially-adapted pointed fangs that can deflate toads that fill themselves with air in an attempt to make themselves larger to avoid being swallowed. They also contain a mild venom that likely helps subdue their prey, though it is harmless to humans.

Eastern Hognose Snake

Eastern Hognose Snake

Eastern Hognose Snake

Seeing the Purple Bladderwort and exploring these incredible habitats is an experience I will never forget. I can’t wait to return in the future to spend more time among the carnivores (large and small) of the Big Thicket.