Hill Country Waterfall

It’s a pilgrimage that many Texans undertake at some point – to see the fall colors of Lost Maples. Despite living in Texas for over 20 years and extensively exploring all corners of the state, it was a trip I had yet to take. This year we finally decided to see what the fuss was about. It would turn out to be an adventure, filled with frustrations and rewards.

Carolina and I left early and made our way to the Bandera Canyonlands, a term used by the nature conservancy to describe the region in the western Hill Country that contains a labyrinth of canyons carved through the limestone over millennia by springfed streams.

We arrived at the Love Creek Preserve in the early afternoon. We were granted special permission to visit this preserve which has limited public access. The Love Creek Preserve is another example of the substantial conservation efforts of The Nature Conservancy in Texas. Here they succeeded in protecting over 2,500 acres of excellent Hill Country habitat, home to rare plants and animals and numerous Texas endemics. The preserve also protects several spring-heads which feed tributaries to the Medina River, which ultimately feeds the Edward’s Aquifer. The Nature Conservancy truly has protected some of the most spectacular places in the Lonestar State.

It was a sunny day, and being early in the afternoon, the conditions were not ideal for photography. I took my gear along anyway, as one never knows what they might encounter in a place such as this. I carried my camera atop my tripod as I descended the precarious canyon walls with little difficulty. I then rock-hopped my way across a wide stream without incident. Then, after casually stepping on an innocuous boulder I somehow lost my footing and went down hard. I was extremely unhappy, as Carolina can attest, but not hurt. Then I looked at my camera, laying lens first in the cobble adjacent to the stream. I feared the worst. Miraculously my camera and lens survived unscathed, but my neutral density filter and circular polarizing filter had both been cracked. I could live without the latter, but the polarizer is a crucial bit of gear for photographing fall color. I was disheartened, to say the least.

I tried not to let this bad news dampen my enjoyment of the small canyon that we had set out to explore. Just being in such a place – taking in it’s sights, smells, and sounds, is a joy and a privilege that I feel fortunate to have experienced. And as the sun drew closer to the top of the canyon walls I was able to capture a sunburst through the leaves of a Bigtooth Maple that quivered in a gentle Autumn breeze.

Hill Country Canyon

As the daylight faded, we bid farewell to Love Creek, for the time being at least. Our base camp, so to speak, for the trip was the Cool River Cabin, located on the Native American Seed farm near Junction. Native American Seed is a fantastic company that grows a huge assortment of native plants and offers seeds and root stock for sale. They rent out the cabin, which is actually a three bedroom house with two porches and a full kitchen! It is a short walk from the Llano River, and contains scenic views and abundant wildlife. I highly recommend staying here!

The next morning we set out to the Caverns of Sonora. It was one of the more extensive cave tours I’ve taken in Texas cave country, and we marveled at the subterranean formations. After exploring the caves we spent some time at the Eaton Hill Nature Center in Sonora. We discovered this little gem by chance, and thoroughly enjoyed the exhibits which include several live rattlesnakes.

As the shadows grew longer we found ourselves at South Llano River State Park. A good portion of the park remained closed due to the unprecedented flooding experienced by the region just a month before our visit. There was still plenty to see, however. Not long after entering the park we were greeted by a large Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) foraging in a mowed area adjacent to some dense brush. It was quite focused on its pursuit of dinner, and barely took a second to lift his head long enough for me to fire off a shot. Armadillos are one of our more entertaining mammals, often allowing for a close approach due to their generally poor senses. When they do finally realize that there is a perceived threat too close for comfort they will suddenly stop their activity, and bolt off, bounding erratically toward the safety of denser brush.

Nine-banded Armadillo

We came upon a group of Woodhouse’s Scrub Jays (Aphelocoma woodhouseii) scouring a juniper thicket as the sun vanished behind the distant hills. These intelligent, expressive birds are a joy to watch as they examine their surroundings. They seem to display genuine curiosity and approach problem solving with some semblance of enjoyment. Until recently these were considered Western Scrub Jays, but were split due to genetic evidence that suggest they, as well as the California Scrub Jay, Island Scrub Jay, and Florida Scrub Jay are distinct species.

There was very little light to work with, and I took the image below at 1600 ISO and 1/200 second. The resulting image was grainy and softer than I would have liked. I debated trashing the image, but decided that I liked the texture and colors on the bird, so I tried to clean it up through post processing. I ended up with an image that i was happy with. As digital photo processing technology continues to advance, I find myself saving more and more images that I would have otherwise thrown away.

Woodhouse’s Scrub Jay

That night, I posed the idea of traveling the three hour round trip from our cabin to a Best Buy in San Antonio to buy a new polarizing filter, and Caro agreed. I am very fortunate to have a wife that encourages my passions so. We returned “home” that evening around at around 11 o’clock, with a new polarizing filter that I hoped would help my lens bring out the colors of the canyons.

The next day broke to gray skies. We were up and out early, packing our things and bidding farewell to the Native American Seed Farm. Our first destination would be Lost Maples State Natural Area. This iconic park is extremely popular from mid October through November, particularly on the weekends, which just happens to be when we arrived. We learned, as we watched vehicle after vehicle pour in, that it had been a less than stellar year for the maples in the park, apparently affected by the heavy rains a month prior. Many of the leaves had simply turned brown and fallen from the trees. The park was certainly beautiful, as we hiked along droves of other leaf peepers, but it did not provide that spectacular autumn color that I had hoped for.

Lost Maples gets its name for the relictual populations of Bigtooth Maple (Acer grandidentatum) that persist in the area. Once more widespread throughout the region, as the glaciars retreated and the climate in the region warmed and dried, the maples were pushed to moist canyons along sprinfed streams and rivers.

The State Natural Area is not the only place to protect remnant groves of Bigtooth Maples however. After spending a couple of hours hiking popular trails, we decided to return to Love Creek. On the way we explored a few county roads to see what we might see. The morning was cold, with temperatures never leaving the 40s. The last thing I expected to find was a snake, however that’s exactly what I expected when we saw a group of Black-crested Titmice going crazy just a few feet off the ground. They were chattering incessantly, crests raised, hopping from branch to branch staring directly at the ground. Shaking off the cold I approached, and saw a gray and yellow striped serpent stretched out across the ground.

It was a young Baird’s Rat Snake (Pantherophis bairdi), not something I had expected to find here at the eastern edge of their range on such a cold November day. They are restricted in range to the Trans-Pecos and western Edward’s Plateau of Texas, and adjacent northeastern Mexico. They are one of our state’s most beautiful snakes, in my opinion, displaying shades of steely gray, yellow, and orange. Despite the cold, this individual was feisty, and once disturbed never backed down from his coiled defensive posture.

Baird’s Rat Snake

After spending some time in the company of the splendid reptile, we continued onto Love Creek the sheltered canyons here were displaying spectacular color not seen at Lost Maples. We marveled at the shades of orange and yellow that glowed like flames brightening the otherwise dreary day.

Bigtooth Maples at Love Creek

My friend David Bezanson of the Nature Conservancy told us where we could find a waterfall that drained the crystal clear springfed water of one of the many canyons that cut into the preserve’s limestone bluffs. It was like an oasis in otherwise semi-arid country. Mosses and Maiden-hair Fern clung to the rock, kept perpetually moist by spray from the falling waters. I could imagine the water at the base of the falls stayed cool, clear, and deep even during the height of summer.

Each angle of the falls provided some unique perspective. The contrast of the aquamarine waters, the bright green ferns, and the yellows of overhanging witch hazel and orange of distant maples painted a scene that seemed almost impossibly beautiful.

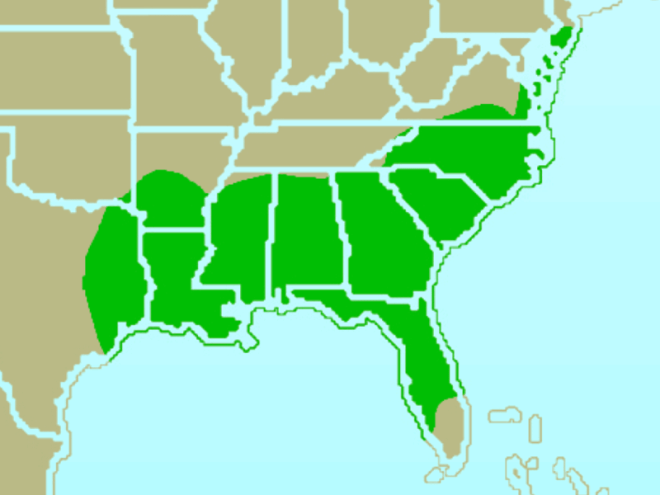

Venturing into the narrow canyon that fed the falls, we found a lush forest that seemed out of place in this region that is knocking on the desert’s door. Towering trees shaded a thick layer of leaf litter that blanketed scattered boulders and smaller rocks. Beneath this leaf litter we found several Western Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon albagula). Another relict of cooler time, the central Texas populations of P. albagula are isolated from the the main portion of the species’s range by hundreds of miles, with the nearest known populations occurring in southwest Oklahoma. Genetic analyses may reveal that this disjunct population is in fact a species unto itself.

Western Slimy Salamanders

The trees here are remarkable as well, and include several other disjunct, relictual species like American Basswood, Chinkapin Oak, and Witch Hazel. They join the Bigtooth Maples, Lacey Oak, Texas Red Oak, Texas Mountain Laurel, Texas Redbud, and more to create a diverse, layered, closed-canopy forest.

As we ventured deeper into the canyon we found the stream’s source. Water was literally pouring out from the base of a massive limestone cliff, nourishing verdant Maiden-hair Fern, and what I imagined to be a profusion of spring wildflowers. The water here is home to an endemic species of neotonic Eurycea. It was humbling to see the literal source of so much life.

Water pours from the base of a limestone cliff, fueling a lush, diverse canyon

Deeper into the preserve we found a wider, drier canyon fed by a different spring. Here the maples were absent, but Texas Red Oak (Quercus buckleyi) provided a splash of color to the scene. I was truly blown away by the beauty of this place, an area unlike any other in the world. I don’t proclaim to know if Heaven exists, but in my book, the Bandera Canyonlands are about as close to Heaven on Earth as one can get.

Bandera Canyonlands