Mountain Short-horned Lizard

Target Species:

Mountain Adder’s Mouth (Malaxis macrostachya)

Wood’s Jewel Scarab (Chrysina woodii)

Mountain Short-horned Lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi)

The sky islands of West Texas have been woven into the fabric of my being. Each trip to these high elevation oases of the desert brings with it a sense of wonder and euphoria, and a longing to return. Since returning from our trip in July, not even a month ago, I have been desperate to get back to the high elevation grasslands, shaded canyons, and montane forests. There is so much to see. Such plant and animal diversity, such natural beauty. Here among the cool mountain peaks I feel at home.

When I approached Carolina with the idea of returning to the Nature Conservancy’s Davis Mountains Preserve for another open weekend in August, it didn’t take much convincing. We decided we would return, and this time we would be bringing our good friends James and Erin Childress with us. So we set out in the blackness of early morning on a great pilgrimage to the Trans-Pecos.

By the time the sun rose, the towering Loblolly Pines and stately hardwoods had mostly vanished in the rearview. As dawn broke they gave way to gnarled post oaks sprawled over verdant grasslands. Gradually the post oak gave way to mesquite, and the grass became more and more sparse, until bare rock seemed more abundant than plantlife. We passed over the Ozona Arch into the desert scrub of the Permian Basin, and finally after what seemed like an eternity, the foothills of the Davis Mountains came into view.

We took our time on the scenic loop, admiring the scenery in every direction, and watching for plants and wildlife along the road. When we finally arrived at the preserve, we stepped out into the cool mountain airs and paused a moment to take it all in. We could see Madera Canyon in the distance, as it worked its way toward the slopes of Mount Livermore, the highest peak in the Davis Mountains, and the fifth highest in Texas.

We visited a moment with our friend and local landowner Gary before venturing into the preserve. We made camp in a flat basin among scattered Alligator Juniper and Pinyon Pine growing above a rich layer of forbs and grasses. Among this herbaceous layer I spotted the purple flowering spikes of Lobelia fenestralis, the Fringeleaf Lobelia. This striking sky island specialist barely enters the U.S. in extreme West Texas and one county in western New Mexico.

Fringeleaf Lobelia

After setting up camp we journeyed into Madera Canyon. We admired the birds as we went, watching as a Common Black Hawk flew from the crown of an Alligator Juniper, and a Montezuma Quail burst from the grasses and across the road before us. We were serenaded by Western Kingbirds, Blue Grosbeaks, and Say’s Phoebes while the occasional hummingbird shot past like a bullet, offering little opportunity to identify it to species.

As we scoured the slopes along Madera Creek in hopes of glimpsing one of the many interesting things that dwell there, I heard Carolina call out that she had found one of my targets. Sure enough, between the large rocks at the base of a Ponderosa Pine was a single green leaf. My search was now narrowed and intensified, as I made my way along the steep, rocky slopes hoping to catch one of these bizarre plants in bloom. I looked and looked, until I saw what I was searching for: the single leaf and ten-inch flowering spike of the Mountain Adder’s Mouth Orchid (Malaxis macrostachya).

Mountain Adder’s Mouth

The Mountain’s Adder Mouth is an orchid of the montane forests of the southwestern U.S. and Mexico. In Texas it is known only from the high elevation slopes of the Davis Mountains. Though the plant itself may reach a foot in height, the flowers themselves are tiny, and a hundred or more may decorate the raceme. This long, narrow raceme has earned this orchid the colloquial name “Rat-tail Malaxis”. We searched the area for more orchids to no avail, and I counted myself lucky to have found such a fine specimen.

Mountain Adder’s Mouth

As the sun vanished behind the distant peaks we slowly began making our way back to camp. In the fading light of dusk we spotted a brown blur moving across the road ahead. Drawing nearer we made out the shape of a large bobcat vanishing into the grass. We paused a moment and watched, hoping that we might catch another glimpse of this elusive feline. Our efforts were rewarded, as it occasionally appeared between breaks in the vegetation as it silently and meticulously made its way through the dark forest of pinyon and juniper.

We arrived back at camp with little light to spare. James and I strung a large white sheet between the branches of two trees a short distance from our site. We then propped a small florescent bulb on my tripod and aimed it at the sheet. Our trap had been set.

As the sheet collected our six-legged quandary we prepared a meal of dehydrated broccoli cheese soup, and settled in to watch the skies. The heavens seemed locked in some violent battle, as tailed balls of light danced across the sky, flying from horizon to horizon. In truth we weren’t witnessing some celestial war, but rather the peak of a perseid meteor shower, when the constellation Perseus scatters massive particles throughout space. When our eyes and necks could no longer take in the wonder of the skies we shut off our light trap and retired for the evening.

We rose early the next morning. The first order of business was photographing a most spectacular creature that we had found the day before. I was lucky enough to catch a fresh Wood’s Jewel Scarab (Chrysina woodii). Carolina spotted the brilliant beetle as it flew about a pecan tree that had been planted at a picnic area in the foothill’s of the Davis Mountains. As this species evolved to specialize on walnut leaves, it is not so surprising that it would also make use of Pecan, a close relative. Anxious to arrive at the preserve, we held onto the beetle to photograph later.

Wood’s Jewel Scarab

Now, in the beautiful early morning light we set it in our viewfinders. I have always dreamed of finding a live Chrysina woodii. A desire that has only been fueled after finding numerous crushed bits and pieces over the years. C. woodii is endemic to the sky islands of West Texas, eastern New Mexico, and northern Mexico. In Texas it has been documented in the Davis and Guadalupe Mountains. The beetles actively feed during the day and are regularly attracted to lights by night.

Wood’s Jewel Scarab

Chrysina woodii is also known as the Blue-legged Jewel Scarab. It’s easy to see why, when admiring its brilliant metallic blue tarsi. C. woodii is named for Dr. Horatio C. Wood, a pharmacologist who also published numerous papers on botany and entomology. Wood collected a number of brilliant metallic green beetles in West Texas and gave them to his friend, George Henry Horn. Horn was a pioneering coleopterist (entomologist specializing in beetles) active in the southwest during the late 1800s. Horn presented the specimens at an entomological congress in 1883, and formally described Chrysina woodii in 1885.

Wood’s Jewel Scarab

The light trap that we set the previous night was a success. Among the flurry of moths that I was woefully under-prepared to identify, Erin spotted a creature of metallic green decorated with bright silver streaks: a Glorious Scarab (Chrysina gloriosa). We held onto it until morning, when we opted to photograph it on the leaves of an Alligator Juniper, one of the primary food sources of the adults. Despite the beetle’s gaudy appearance, it is incredible just how cryptic it was among the blue-green juniper leaves.

Glorious Scarab

After breakfast and our coleopteran photo session we set back out into Madera Canyon. Once again we paused to admire the incredible array of birds that flit about the trees, filling the mountain air with their sweet songs. In the early morning hours the showy blooms of the Torrey’s Crag Lily (Echeandia flavescens) had opened. By midday they will have closed, and the plants will become invisible among the sea of grass that surrounds them.

Torrey’s Crag Lily

Along the bases of the large rocks lining Madera Creek I spotted the succulent Havard’s Stonecrop (Sedum havardii). This species is known in the U.S. only from the Davis and Chisos Mountains of West Texas.

Havard’s Stonecrop

Deep in Madera Canyon we turned into one of the many side canyons formed by ephemeral streams feeding Madera Creek. We were spread out along the gradual slope when we heard Carolina call out “snake”. I’ll admit that it took me a moment when she struggled to draw our attention to the serpent before her. But sure enough, there, among a downed alligator juniper sat a Mottled Rock Rattlesnake (Crotalus lepidus lepidus). The cryptic viper was nearly invisible due to its remarkable camouflage. We all delighted in observing and photographing the beautiful reptile. Despite its potent venom, it remained docile throughout our encounter, and would not display even the slightest bit of aggression toward us.

Mottled Rock Rattlesnake

We bid the rattlesnake farewell, and ventured deeper into the canyon, until it flattened out into a broad high elevation basin. The ground here was littered with small rocks. Soon we came to realize that here some of the rocks move. James was the first to catch movement among the pebbles, as one stone seemingly jumped out of his way. Baffled, we looked closer, only to reveal that what looked like nothing more than one of the basin floor’s countless stones was actually a neonate Mountain Short-horned Lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi).

Mountain Short-horned Lizard

It soon became clear that these tiny lizards were all around us, and within the span of an hour we saw more than a dozen. Their abundance that day is likely a product of their reproductive biology. The females give live birth to as many as 40 or more of these living stones in July and August. The neonates are then left to fend for themselves as they scatter about the surrounding area. It is truly remarkable just how well-camouflaged these tiny dragons are.

Mountain Short-horned Lizard

Mountain Short-horned Lizards

Spotting the baby lizards became something of a contest. And while I was genuinely thrilled to have seen them, I couldn’t help but hope that we might encounter an adult. Deeper into the basin we pushed until a distant rumble drew my attention to the peaks behind us. Behind the mountains a massive storm was building, sending broad black clouds towering to the sky. It was fast approaching. Deciding that we would prefer not to wait out a storm at the base of some pine or juniper we decided to retrace our steps.

The storm drew nearer and nearer still as we retreated toward the safety of my truck. Between the cracking thunder that echoed from the canyon walls, Erin called out “a big one! A big one!” My eyes followed her finger to the rocky earth, where it took them a moment to spot the large Mountain Horned Lizard sitting still among the stones.

Mountain Short-horned Lizard

Despite the impending deluge, we settled in to admire this incredible creature. Thunder rang and the sky darkened as our shutters closed in rapid succession, forever freezing a moment of the lizard’s life in time. I couldn’t help but imagine what a bizarre, frightening experience this must have been for it. Fortunately, for a lizard photographer, at least, most horned lizards rely on their camouflage as a defense mechanism, and are prone to hunker down in an attempt to avoid being seen.

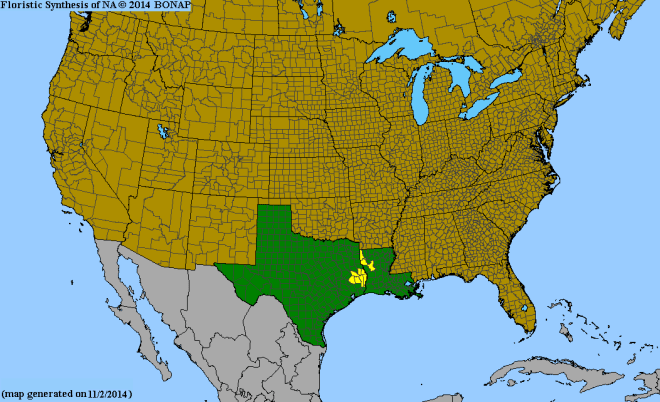

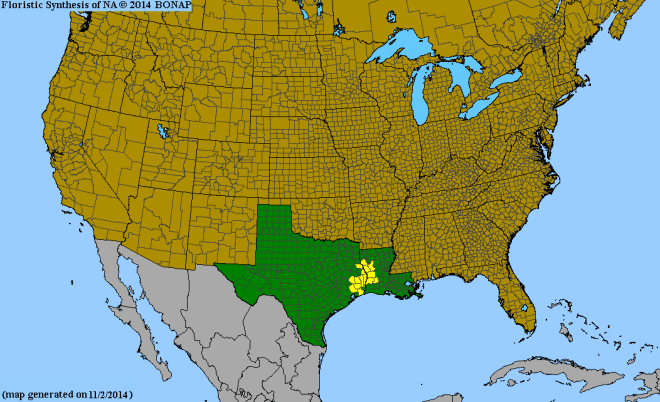

As a group, the horned lizards of the genus Phrynosoma are often referred to as “horny toads”. A misnomer, of course, as toads are amphibians and these are very much reptilian. Phrynosoma hernandesi is among the most widespread of the horned lizards, occurring across much of the western U.S. and Mexico and into southern Canada. They generally occur in high elevation woodlands, prairies, and savannahs in the southern portion of their range, and grasslands and forested foothills to the north. In Texas they are primarily restricted to the Davis and Guadalupe Mountains, with a few scattered populations in other ranges around El Paso.

Mountain Short-horned Lizard

The Mountain Short-horned Lizard is one of a number of the Phrynosoma that is able to shoot blood from the corner of its eye. This tactic appears to primarily be utilized against canine predators. Fortunately it did not deem us a sufficient enough threat to warrant such an attack.

Mountain Short-horned Lizard

We spent some time in the lizard’s company, and hastily returned to the truck. On four wheels we were able to get ahead of the storm, and after a lunch of tuna sandwiches we set out to explore the scenic loop that winds around the Davis Mountains. We stopped a moment at the McDonald Observatory, and continued on to Fort Davis. As we neared the small grocery store in town, the rain finally caught up with us. It is a magical experience, rain in the desert. The dusty earth dampens and releases its sweet, distinctive aroma to the air. We soaked in the rain, both literally and figuratively, as we restocked some supplies and prepared to continue on the loop along the southern and western edge of the Davis Mountains.

The rain was letting up as we spotted a large Pronghorn buck and his harem of six does not far outside of Fort Davis. We watched them as lightning descended distant clouds on the horizon. After spending a few moments with North America’s fastest land mammal, we continued down the road where we saw a large Mule Deer Buck browsing among the cholla and desert grasses.

Scaled Quail and Roadrunners darted across the road before us as we made our way further down the scenic loop. We stopped at the Point of Rocks Roadside Park, where James chased after a Canyon Towhee with his camera, Carolina and Erin explored the massive rock outcrop, and I prepared a dinner of macaroni and tuna. The sun had begun to peak through the clouds, casting its rays to distant rain showers that transformed its light to a myriad of brilliant colors arching across the sky. After dinner we returned to the loop where we found a number of Western Diamondback Rattlesnakes before returning to our campsite around 11 pm.

The next morning we broke camp and said farewell to the Davis Mountains Preserve. Our time in this remarkable sky island, however, was not yet over. We were off to visit Gary at his property on the other side of the range. He lives in a remote corner of Limpia Canyon far from paved roads. The creek that helped form the canyon was running. Its crystal clear waters pouring over boulders among the towering Ponderosa Pines looked more a scene from Colorado than West Texas. We would later learn from Gary that it might run only a month or two out of the year.

I had visited the forested canyon on Gary’s property last year and I couldn’t wait to show James and Erin this hidden paradise. I hoped that we might spot some Giant Coralroot Orchids (Hexalectris grandiflora). We had looked for them on the preserve, but only succeeded in finding spent, wilted flowering stalks. As we followed Gary up the canyon he regaled us with stories of the “Republic of Texas“, a militia group that believed that Texas should never have become part of the United States, and took it upon themselves to secede. There were still signs and artifacts of their presence on his land.

It wasn’t long before we spotted the first group of coralroots. It was a cluster of fresh plants, but unfortunately the flowers were all closed and drooping, a phenomenon that is fairly common among the genus Hexalectris. We took their presence to be a good sign and continued on. We (more accurately Carolina) spotted several Mountain Adder’s Mouth Orchids. They seemed to be more numerous here than in Madera Canyon.

Just as we were debating turning around, James pointed out a splash of color in the deep shade of some low hanging branches of an Emory Oak. It was a pair of Giant Coralroots in perfect bloom. I had grown accustomed to seeing only one or two open flowers on any given individual at a time. One of these, however, had three that were clustered closely together. After a long, uncomfortable photo session we bid the orchids farewell and returned down the trail as an afternoon thunderstorm, typical of the monsoon season, began to build behind the peaks surrounding the canyon.

Giant Coralroot

Gary invited us in for snacks and alcoholic cider, an offer that was hard to turn down. We enjoyed his company and knowledge of the area’s natural and cultural history. After visiting a while James and I set out to photograph the wealth of scenery around Gary’s home when James spotted a peculiar pattern on a nearby boulder. “Do you see what I see?” he asked pointing at the rock. It took a moment, but finally I saw it – a young Mottled Rock Rattlesnake resting still and silent. In that moment our photographic priorities changed and we set about capturing the beautiful snake. Just as we were finishing the building clouds reached their critical mass and began releasing their moisture in the form of an afternoon downpour.

Mottled Rock Rattlesnake

We bid our reluctant “good bye’s” to Gary and the mountains he calls home. That night we would descend from the sky islands and make our camp in the desert scrub around Lake Balmorhea. Here we watched a large group of Clark’s Grebes on the water, while we listened to a Pyrrhuloxia call from among the impenetrable thorn fortress of the surrounding desert. Carolina spent the evening rock hounding in search of the elusive Marfa Agate while James and I looked for signs of life and Erin enjoyed one of her favorite books in the spectacular setting of the Chihuahuan Desert. Carolina was lucky enough to find a few choice pieces of agate while James and I spotted a number of large Tarantula Hawks and Western Green June Beetles. All of our attention, however, soon turned to the horizon, where the setting sun painted a rainbow on the black clouds of a distant thunderstorm. It was a fine final chapter to an incredible Trans-Pecos adventure.

A distant thunderstorm rages over the desert scrub near Balmorhea.