Thanks in part to an exceptionally early spring this year, I have been able to get a good start of my list, knocking off four species in February. These species include:

Woolly Sunbonnets (Chaptalia tomentosa)

Texas Saxifrage (Micranthes texana)

Texas Trailing Phlox (Phlox nivalis ssp. texensis)

Spring Coralroot (Corallorhiza wisteriana)

I’m slowly making progress on my 2017 Species List

Though tracking down the species on my list has become a priority in my explorations of the natural world, I could never neglect the special places and familiar species that I have come to love over the years. I look forward to seeing them each year, and regardless of how many photos of a given species I might have, I can never resist the urge to try and capture new details, compositions, and natural history aspects.

I spent much of early February exploring the woods with my good pal James Childress. On one such outing we were lucky enough to find a gravid Smallmouth Salamander (Ambystoma texanum) under a log in a false bottomland.

Smallmouth Salamander

A few days later I received a text message from James that included a photo of a seldom seen sight: an East Texas tarantula. Tarantulas are typically associated with deserts, however the Texas Brown Tarantula (Aphonopelma hentzi) ranges as far east as East Texas and western Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri. It is an unexpected thing to see one in the forests of the West Gulf Coastal Plain, but here they persist, though their populations seem to be declining. I have spoken to lifelong residents of the area who remember seeing many as children, and few to none in the past 20 years. James found this female, identifiable as such by its large abdomen, crawling in his driveway one evening. He was kind enough to hold onto it so that I may photograph it. It’s only the fourth tarantula I have seen in the Pineywoods, and the only female.

Texas Brown Tarantula

Texas Brown Tarantula Portrait

When I met James for our tarantula photo session he brought another surprise with him – a Banded Tiger Moth (Apantensis vittata) that had been attracted to his garage lights. This boldly patterned moth is equipped with bright hindwings that it will flash in an attempt to intimidate a potential predator.

Banded Tiger Moth

After admiring these invertebrates we went on to visit a rich mesic stream bottom that supports a variety of spring ephemeral herbs. Representing what is essentially the southwestern limit of the range of eastern deciduous forests, East Texas is on the periphery of the range of a suite of spring ephemerals. Spring ephemerals as a group are adapted to deciduous, hardwood forests, where they can carry out the majority of their life cycle in the early spring, when an abundance of sunlight reaches the forest floor prior to leafout of the canopy. Species are generally less common on the periphery of their range. As a result of this coupled with habitat loss over the past century and a half, several of these species have become rare in East Texas. These eastern forest elements are perhaps my favorite part of the Pineywoods.

The White Trout Lily (Erytrhonium albidum) is one such spring ephemeral. It’s leaves begin to emerge by early February and are mostly gone by late April. Members of the genus Erythronium are known as trout lilies in the eastern U.S. due to the resemblance of their leaves to the skin of the brook trout. In the western U.S. they are often known as fawn lilies, as the leaves look like the spotted pelage of young fawns. In Europe, they are usually referred to as dogtooth violets, a reference to the shape of the underground bulb. Erythronium albidum is rare in the Pineywoods, with larger populations in the Post Oak Savannah and Dallas region.

White Trout Lily

One of my all-time favorite flowers is the Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis). Another characteristic spring ephemeral of the eastern deciduous forests, it too is rare in Texas. In a typical year I can expect to see Bloodroot blooming at this site around February 20. This year many were already in fruit on February 10. Bloodroot is named for the thick red sap that oozes from it’s root when injured. This sap has a myriad of health benefits, and its abrasive nature makes it a good ingredient in toothpaste. These desirable properties have likely led to over collection of this species, adding to its rarity in the state.

Bloodroot

One of the more difficult to spot spring ephemerals is the Southern Twayblade Orchid (Listera australis). It’s tiny brown stems and flowers are practically invisible against the leaf litter. They are only betrayed by two green leaves near the base of the stem.

Southern Twayblade Orchid

Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica) is an abundant spring ephemeral throughout much of East Texas. Though it is easiest to find on lawns and other cleared areas, I prefer to photograph the individuals deep in the forest, where they are less commonly seen.

Spring Beauty

Carolina Jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens) is a common woody vine of the southeastern U.S. It slowly works its way from the ground to the canopy, and in early spring it paints the forest yellow with its large, tubular flowers.

Carolina Jessamine

It is interesting just how many species have Carolina in their common name, or some variation of it in their specific epithet. The reason is because many species native to the eastern U.S. were initially described in the far east, including the Carolinas. Virginia also frequently occurs in taxonomic vernacular. I take it as a good sign that my wife lends her name to so many pretty things.

Last Sunday Carolina and I had a very productive outing chasing after spring ephemerals in Deep East Texas. We covered a lot of ground and saw a lot of species. One of the most striking was the Birdfoot Violet (Viola pedata), named for its leaves which bear a superficial resemblance to bird’s feet. These are our largest violets, easily twice the size of the more common species. It occurs in scattered populations in East Texas, where it favors open dry mesic mixed pine-hardwood forests.

Birdfoot Violet

The Wood Violet (Viola palmata) prefers slightly moister sites with a greater hardwood element. With a few exceptions (Birdfoot Violet being one of them) the flowers of East Texas’s violets are difficult to differentiate. Wood violet is identified by its deeply lobed leaves.

Wood Violet

Violet Woodsorrel (Oxalis violacea) was also blooming. This native is often mistaken for the much more common Pink Woodsorrel (Oxalis debilis), a native of South America.

Violet Woodsorrel

The occurrence of the Louisiana Wakerobin (Trillium ludovicianum) in Texas was only recently discovered, as botanists closely examined a group of unusual-looking sessile-flowered Trillium. They had long been masquerading as the Sabine River Wakerobin (Trillium gracile). Differentiating the two species is a painstaking task that requires close examination of the flowers.

Louisiana Wakerobins

Trilliums are classic spring ephemeral flowers that occur in rich woods across much of the country. Their center of diversity, however, is in the eastern deciduous forests. Trillium ludovicianum occurs on rich mesic slopes dominated by American Beech and other hardwoods. Since its discovery in Texas, the Louisiana Wakerobin has only been found at a handful of sites.

Louisiana Wakerobin

Louisiana Wakerobin

While exploring the rich woods I stumbled upon this scene, and could not resist. The perfect clump of trillium with the similarily rare Wild Blue Phlox (Phlox divaricata) in the background represents to me, what is most magical about spring – exploring rich forests in search of ephemeral forbs and other interesting things that are awakening following a long period of dormancy. To me, the forest feels most alive in the springtime, and so do I. This shot ended up being one of my favorites from 2017 thusfar.

Rich mesic forest with Trillium ludovicianum and Phlox divaricata

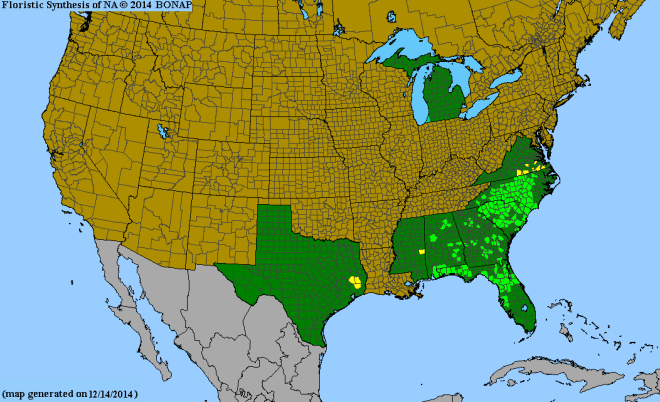

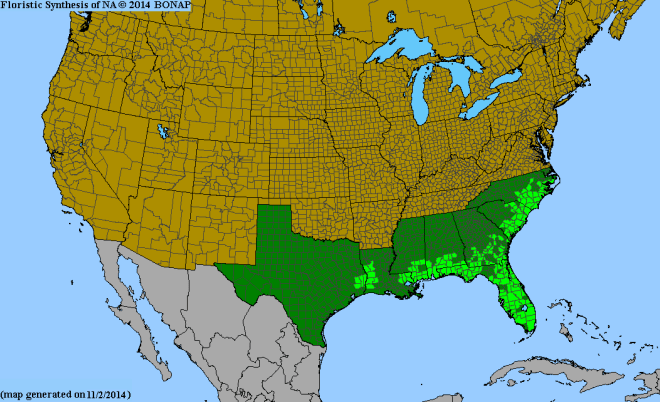

This site is also one of the few areas where Wild Blue Phlox can be found in Texas. It too is a typical denizen of the rich eastern deciduous forests that reaches the southwestern extent of its range in East Texas. And like so many of the previously mentioned species it is rare here.

Though one might not think it so if they were to visit this particular spot, where it blooms in spectacular profusion on the banks of a clear East Texas stream.

Flowering trees are at their peak this time of year, and many species are beginning to decorate the understory with splashes of white and pink. Pictured below is one of the hawthorns (Crataegus sp.). Though habitat gives some clue, identification to species is difficult without the leaves present.

Hawthorn in Bloom

Near the hawthorn, Carolina and I stopped a moment to admire this beautiful redbud along a small ephemeral stream. Though it was getting late and the day was growing dim, the pink blossoms of the Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) brightened the woods around us.

Eastern Redbud

I spent February busily pursuing plants, but I have not neglected the other taxa of my list. Carolina and I continue to visit the local otter population on a weekly basis. Though we have not yet seen them, Carolina’s remote camera captured some incredible video of a male scent marking. Unfortunately I’m unable to upload it here, but I will leave you with the following image, otter tracks along a stream near the Trillium ludovicianum and Phlox divaricata site. Though I have yet to capture one on camera, the elusive river wolf continues to make its presence known.

American River Otter Tracks