Target Species: Saltmarsh False Foxglove (Agalinis maritima)

Saltmarsh False Foxglove

The Upper Texas Coast is a naturalist’s paradise. It is one of the country’s premier birding sites, and harbors an interesting flora and fauna including many species that are limited to coastlines and their associated habitats. This region was historically largely a patchwork of coastal prairie, freshwater marsh, brackish marsh, and saltmarsh. Trees and woody vegetation was primarily limited to larger river drainages. Today the habitat has been heavily modified, however remnants of historic vegetation still remain.

Saltmarsh False Foxglove

I had previously observed the Saltmarsh False Foxglove while passing through bands of saltmarsh leading to the beach. For whatever reason I never stopped to photograph it, despite the fact that it was an interesting species restricted to a thin band of habitat directly adjacent to the Gulf and Atlantic coasts of North America. Here it occurs in tidally influenced saltmarsh.

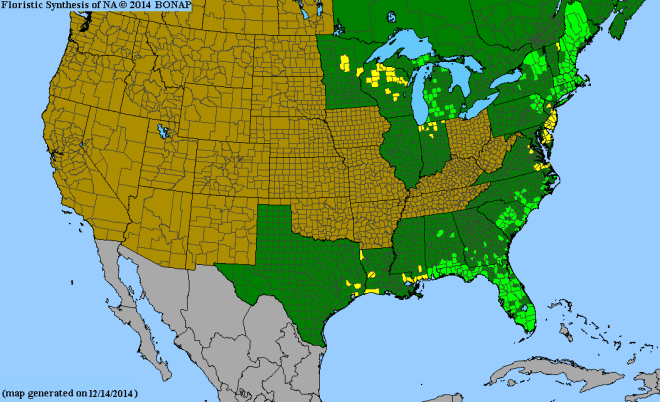

County-level distribution of Agalinis maritima from http://www.bonap.org

This year I made a point to capture some images. Last weekend Carolina and I took a trip to the Upper Texas Coast. The first evening of our trip we passed through saltmarsh where I had seen it in bloom around this time last year. I was disappointed, as I didn’t see any blooms. I thought that I had missed my best shot at checking Agalinis maritima off my list. The next morning, however, while revisiting the beach I saw several in bloom. I came to the conclusion that the blooms open in the morning, and throughout the day as the relentless coastal winds hammer the marsh the blooms quickly fade and fall from the plant. The wind made photography a challenge, but I was able to capture a few images of the Saltmarsh False Foxglove’s beautiful, bizarre-looking flower.

Saltmarsh False Foxglove

There were many other showy plants blooming alongside my target. One of the most striking was the Texas Bluebells (Eustoma exaltatum). This is a wide-ranging species that seems to thrive in the coastal prairies and drier margins of the saltmarsh, though they can be found well inland in open habitats as far north as Wyoming and North Dakota.

Texas Bluebells

The large, bright blooms of the Saltmarsh Morning Glory (Ipomoea sagittata) were also prevalent. The blooms open in the early morning and are mostly closed by early afternoon.

Saltmarsh Morning Glory

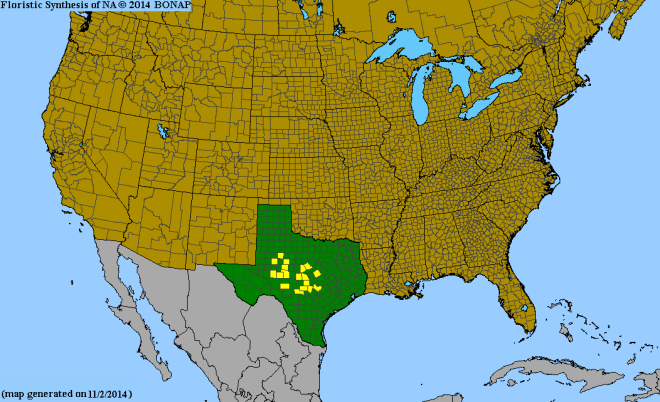

Plentiful rains prior to our visit resulted in an abundance of rainlilies (Cooperia spp.). I was excited to discover that a few were the uncommon Traub’s Rainlily (Cooperia traubii), which is limited to a few coastal and near coastal counties in Texas and extreme northeastern Mexico. It can be differentiated from the similar, more widespread Evening Rainlily (Cooperia drummondii) by it’s elongated style, which extends well beyond the anthers. The style of the Evening Rainlily is either shorter than the anthers, even with the anthers, or barely longer.

Traub’s Rainlily

County-level distribution of Cooperia traubii from http://www.bonap.org. Yellow counties indicate that the species is present and rare.

The taxonomy of prickly-pears (Opuntia spp.) is a bit of a mess. Experts offer differing opinions of how the various species and populations should be classified. The prickly-pears of the upper Texas Coast follow this pattern. Two species are especially contentious. Some experts suggest that these cacti are individuals of the more widespread Opuntia lindheimeri and Opuntia stricta, while others suggest that there are two species endemic to the Upper Texas Coast: Opuntia bentonii and Opuntia anahuacensis. If Opuntia bentonii is a valid taxon, the image below is of this species.

Opuntia sp.

Venturing less than a mile from the coast the marsh slowly transitions from salt to brackish to fresh water. At the margins of a handful of freshwater marshes in the Upper Texas Coast a real gem of a plant can be found: the Fewflower Milkweed (Asclepias lanceolata). The Fewflower Milkweed is a species of the coastal plain that reaches its western limit in Southeast Texas. Here it historically occurred in wetland pine savannahs and wet coastal prairies. Today it exists in only a handful of populations in the Big Thicket and along the Upper Texas Coast.

Fewflower Milkweed

Fewflower Milkweed

Blooming in profusion within the freshwater marsh were scores of Swamp Rosemallow (Hibiscus moscheutos). The spectacular blooms of this species open fully in the early morning, and close by the afternoon.

Swamp Rosemallow

Every trip to the Upper Texas Coast provides unique, memorable encounters with the natural world. There are several other species on my list that call this region home, and with any luck I’ll return soon to seek them out.

Retreating tides and advancing clouds on the Upper Texas Coast

Retreating tides and advancing clouds on the Upper Texas Coast